Have you noticed the drop in visibility across the Front Range over the last few weeks? This haziness is actually smoke from a handful of wildfires burning hundreds of miles to our southwest. This may only be a taste of things to come later this summer as parts of southern Colorado and the Intermountain West have recently shifted into the penultimate drought classification. We provide an update on the hydrological situation and explain why we believe the monsoon will arrive late to Colorado this summer.

At a Glance:

- Wildfires to our southwest continue to pump light to moderate smoke into the Front Range

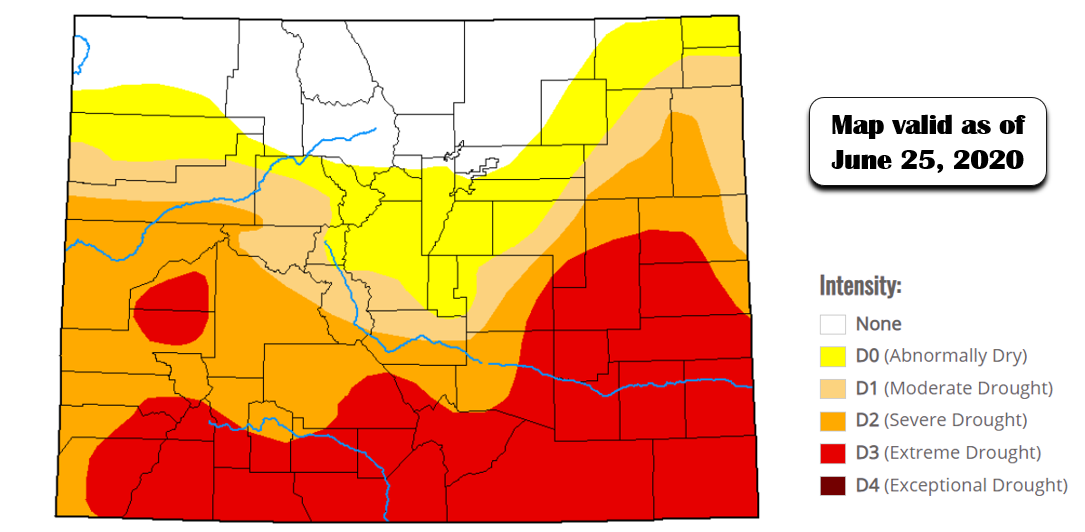

- Over the last 12 months, drought has expanded from 0% to 68% coverage in Colorado

- Seasonal snowpack is melting out quicker than normal in many Colorado mountain ranges this summer

- The onset of monsoon season will likely be delayed by a week or more in our area, targeting the mid to latter part of July

- A La Niña is developing and this may reduce precipitation in our area through summer and early fall

Help support our team of Front Range weather bloggers by joining BoulderCAST Premium. We talk Boulder and Denver weather every single day. Sign up now to get access to our daily forecast discussions each morning, complete six-day skiing and hiking forecasts powered by machine learning, first-class access to all our Colorado-centric high-resolution weather graphics, bonus storm updates and much more! Or not, we just appreciate your readership!

T

here has been a lot of buzz around the Saharan Dust Cloud that impacted the eastern United States over the last week, but it has been a hazy last few weeks across Colorado, too. All it took were a handful of large wildfires igniting to our southwest and the views of our majestic snow-capped peaks became clouded. This is the scene at sunrise from the top of Pikes Peak just a few days ago.

The smoke isn’t as pronounced this week as it was previously in Boulder and Denver, but there is still plenty of smoke to go around as seen in the total column smoke forecast animation below from NOAA’s HRRR-Smoke model. Light to moderate smoke currently encompasses much of the central United States and also eastern Colorado.

HRRR-Smoke vertically-integrated smoke forecast animation for Monday into Tuesday this week (June 29-30). You can trace the plethora of smoke across the country back to a handful of large fires burning in the Desert Southwest

With the worst of the fires still far from contained, this trend will likely continue through the summer into early autumn.

High-resolution satellite imagery from GOES-16 of several large wildfires burning in Arizona and New Mexico back on June 17, 2020.

Drought expands, snowpack wanes

After a near-average winter and spring, at least precipitation-wise, drought has remained suppressed across NORTHERN Colorado. Unfortunately, the good news ends there. The same cannot be said for the SOUTHERN tier of the Rocky Mountain state, where drought has only intensified over the last six to nine months. Portions of southern Colorado have recently progressed into the second worst drought classification as defined by the United States Drought Monitor…a category they call “extreme”.

Colorado has become one of the most drought-stricken states in the country, only bested by Utah and Oregon at the moment (and New Hampshire, but does that really count as a state?).

The time series below shows the areal percentage of Colorado contained in each drought category over that last 14 or so months. One year ago in June of 2019, Colorado was completely free of any drought classification. This was the first time this had happened since 2001. Today, more than 82% of the state holds a drought classification. More astonishingly, 33% of the state is experiencing advanced drought (categories “extreme” or “exceptional”).

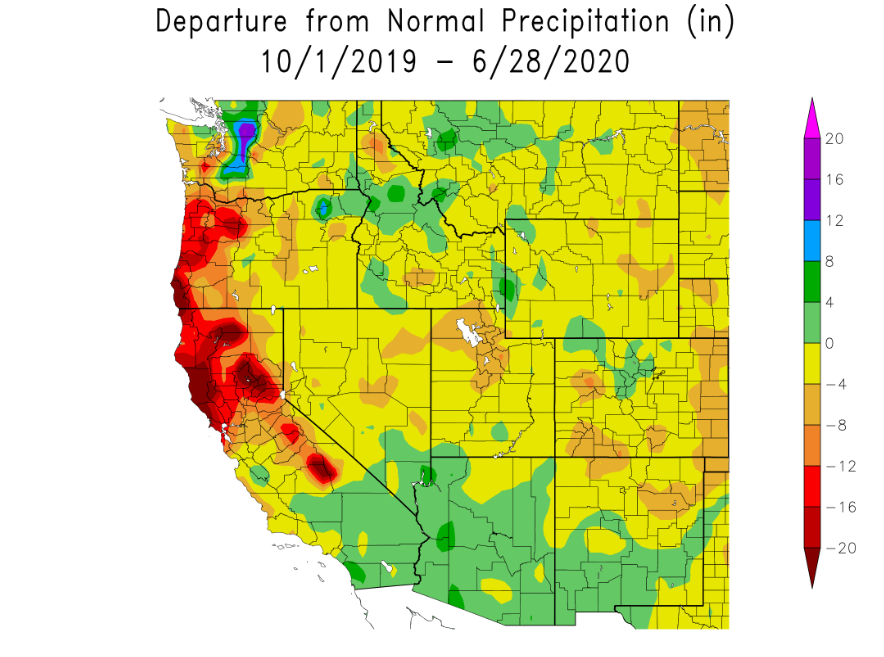

It’s no wonder that drought has overtaken the southern part of the state. Since the beginning of the water year back on October 1st, rain and snow have been very hard to come by, with precipitation totals less than 70% of normal being widespread in southern Colorado. In particular, a very dry late-winter and spring has led to the now perilous predicament at-hand in those areas.

The map below shows the Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) for the entire winter and spring. SPI is used to compare precipitation as it relates to “average” over regions with vastly different climates. Southern Arizona, New Mexico and SoCal did very well this winter. Southern and far eastern Colorado? Not so much.

Here is the time series of snowpack for the South Platte River basin this (water) year. This is the watershed that includes Denver, Boulder and the northern Front Range. By and large, we had an excellent snow year in north-central Colorado with snowpack running above normal nearly the entire season. Sure the peak occurred a few days ahead of schedule, but that apex was around 120% of normal. A warm and relatively snow-free May led to a steep decline during late-spring, but again, that is totally normal.

Across southern Colorado, the narrative was much bleaker with peak snowpack finishing below normal, and the overall peak occurring several weeks ahead of schedule. This early peak combined with a warm and dry spring led to snowpack “running out” several weeks to more than a month early in some areas.

If you’re planning on heading south and west to catch the beautiful wildflowers this year, go earlier than your typical schedule due to the waning snowpack. We’ve heard that conditions are exceptional right now in the San Juans with most flowers in full bloom.

Throughout Colorado and the West, most of the water needed for agriculture, drinking , and other uses comes from mountain snowpack, which melts in spring and summer and runs off into rivers and fills our reservoirs. Over the past 70 years, snow has been melting earlier in the year, and more late-winter precipitation has been falling as rain instead of snow. The snow season that unfolded in southern Colorado this year is slowly becoming the new normal due to the changing climate.

A significant portion of the western United States is experiencing drought at the moment. This includes southern Colorado, Utah, northern Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada and northern California. Ironically, most of the major fires that have flared up so far in 2020 have NOT been in locations impacted by drought. This is even more worrying.

Western United States drought conditions as of June 25, 2020 (Source: United States Drought Monitor)

Locations to our south and west will be facing a harsh fire season ahead with conditions worsening by the day. Our predominant wind direction throughout the summer in the lower to middle atmosphere is out of the southwest. You can probably guess where all the smoke will end up…right on our doorstep.

Will monsoon season arrive late this year to Colorado?

Hope for any drought relief may have to wait a little longer this year. Mid and long-range weather models predict a delay in the onset of monsoon season across the American Southwest with a stagnant and somewhat unfavorable pattern taking hold for the first week or two of July.

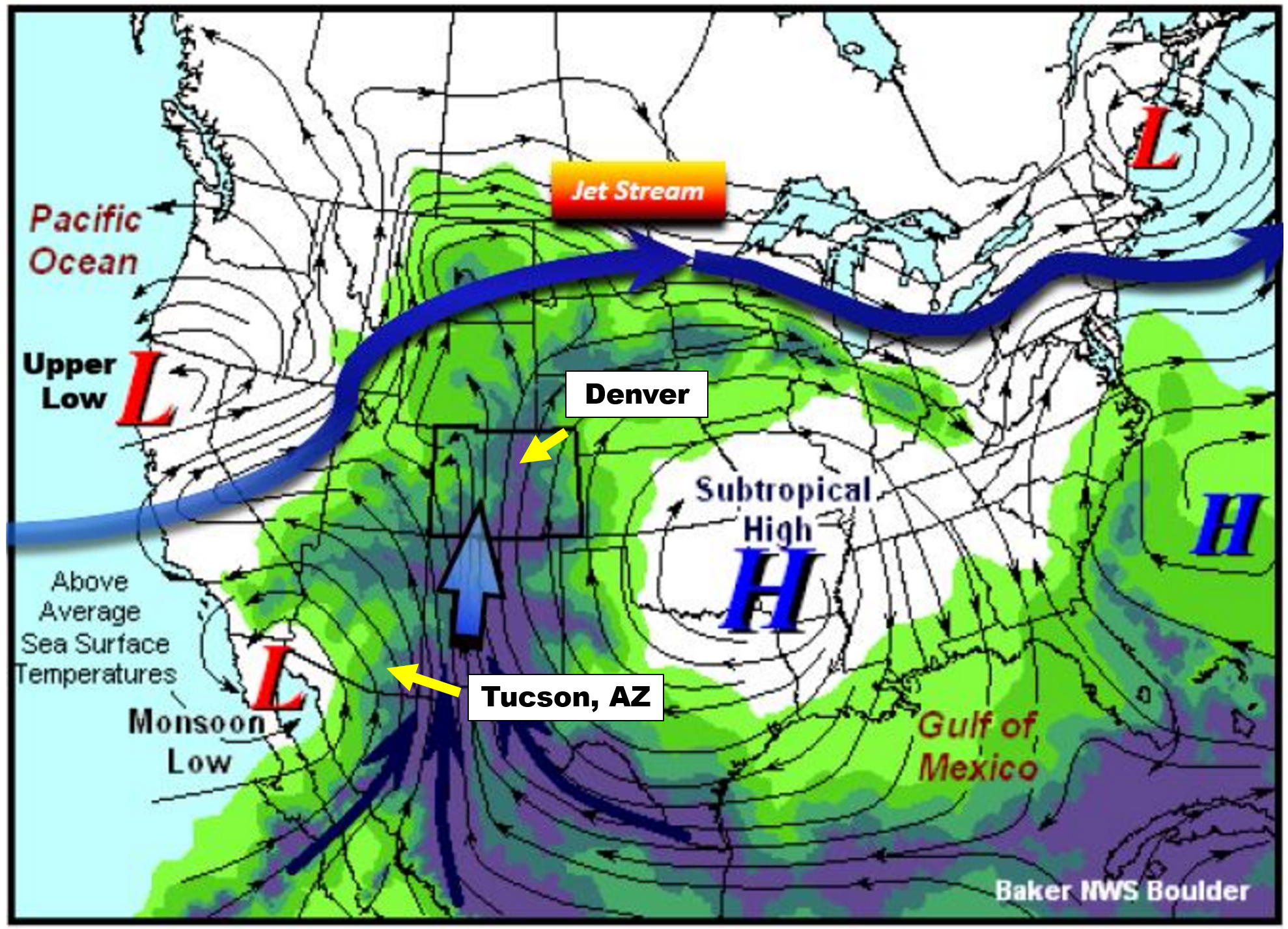

Let’s first begin with examining how the monsoon typically develops. The diagram below shows the usual set-up for what is known as the North American Monsoon, a seasonal shift in the winds that happens every year across northwestern Mexico and the southwestern United States. A “monsoon” low pressure in southern California often teams up with high pressure in the southern United States to funnel relatively large quantities of subtropical moisture northward into the Desert Southwest. This moisture is key to forming those daily thunderstorms that are a staple of Colorado’s summer months. Along with the increased chance of daily thunderstorms, the monsoon brings more dangerous alpine hiking conditions, frequent evening rainbows, warmer nights, more lightning to spark wildfires, and “stickier” air overall.

Officially, monsoon season across the American Southwest begins on June 15th and runs until September 30th. However, much like hurricane season, the official seasonal dates act only as rough guidance and do not necessarily reflect actual atmospheric conditions from year-to-year.

One way that we can track the true arrival of the North American Monsoon is to monitor surface dew points in southern Arizona. Cities like Tucson, which is just 60 miles from the Mexican border (see location above), are much closer to the source of the moisture than we are here in Denver. The moisture more-or-less has to pass through Tucson as it moves northward into the United States. Tucson is also a pivot-point for the moisture plume itself. Think of Tucson as the “faucet”, with a “hose” of moisture wandering northward. Sometimes the hose is over Nevada, other times it meanders over Utah, and Colorado as well.

While our monsoon is sporadic throughout July and August here in Colorado, the faucet is nearly continuous for Tucson. For this reason, despite being a full-on desert, Tucson actually sees more monsoonal rainfall than Denver on average and has a more predictable and consistent monsoon climatology.

It is largely agreed upon that monsoon season’s true start is when the average daily dew point in Tucson is at least 54 degrees for three consecutive days. This parameter is closely monitored by meteorologists and residents of that area. We can’t blame them…July’s average rainfall exceeds the combined total for March, April, May and June in Tucson (above plot on the left). The monsoon is a much bigger reprieve for them than it is for us, especially considering the edge it can take off of those 100+ degree afternoons!

The graph below shows the daily average dew point values at Tucson Airport. The blue line is the actual data from June 2020 so far. The red line is climatology and the green line is the coveted 54-degree threshold for the monsoon. As you can see, Tucson has been very dry of late with daily average dew points running almost entirely below normal since early June.

From the graph below, where the red and green lines come together, the typical beginning of monsoon season in Tucson is around July 7th or so.

While the seemingly big spike yesterday in Tucson’s dew point may seem promising, it isn’t the monsoon gearing up. The National Weather Service in Tucson is hyped for an increase in subtropical moisture these next few days, even going as far as calling it “monsoonal moisture”. We can’t blame them, though. The weather in Tucson is pretty darn boring nine months out of the year. Their excitement for the monsoon has been building for quite some time!

At BoulderCAST, we are not as optimistic as them. The main reason for the sharp increase in moisture is due to the now remnants of Tropical Depression Four-E off the coast of Baja California.

This was the view of TD-4E from GOES-West on Tuesday, just before the final advisory was issued for the dying tropical low.

This tropical system’s large counter-clockwise circulation is reaching deep into the subtropics to pull warm and moist air northward through Mexico and into Arizona and New Mexico.

A true monsoon is a seasonally persistent, broad-scale weather pattern that needs to exist outside of any one tropical cyclone. We hate to be the bearer of bad news, but this type of setup just isn’t there yet. Based on long-range model guidance, it isn’t going to come in the next 10 to 14 days either. The latest GFS ensemble 500 mb height anomaly forecast animation is shown below. A persistent area of high pressure is predicted retrograde (move westward) and sit across Arizona and New Mexico for the entire duration of this animation (which ends on July 10th).

This is a very poor position for that high to sit as it essentially cuts off the flow of moisture into the Desert Southwest entirely, making monsoon development not only challenging, but nearly impossible.

The forecast animation below is for moisture anomaly from the same cluster of model runs. After the initial surge of moisture these next few days this week (aided by the remnant tropical cyclone), moisture quickly wanes and starkly drier conditions return. The monsoon doesn’t appear imminent and by our count will arrive at least a week late, if not longer.

With most signs pointing to that high pressure system setting up directly over Arizona and New Mexico this weekend and persisting into mid-July, the Climate Prediction Center’s latest outlook for the month of July is not surprising. They paint a swath of elevated likelihood of dry conditions for areas near and just east of the high pressure center. This includes the entire state of Colorado.

The Climate Prediction Center also agrees with our assessment that the monsoon will be delayed in Colorado for sure (and perhaps much of the Southwest):

"Over the Southwest, there are conflicting signals among the various models and tools as to how pronounced the onset of the Southwest Monsoon will be. Forecast troughing along the central West coast is not conducive for the climatological development of the Southwest monsoon ridge and so odds for a delayed and weaker onset of the Southwest U.S. monsoon are elevated and so favor enhanced odds for below-normal rainfall in this region for July. Perhaps the best compromise for now is to favor near-median rainfall across far southern portions of Arizona and New Mexico, with scattered showers and dry thunderstorms expected only for these far southern locations."

Furthermore, we’re slightly concerned about a recent trend towards La Niña conditions in the tropical Pacific Ocean. Notice the cool water temperatures extending westward from South America along the Equator. This is the signature of a La Niña, something we haven’t seen this time of year since 2016.

We’re still ENSO-Neutral right now, but the forecast is looking like a La Niña could fully develop as the summer progresses into early autumn. A La Niña pattern tends to inhibit tropical cyclone development in the Eastern Pacific Basin. As you know, the remnants of Eastern Pacific hurricanes can and often do impact Colorado, providing at least the potential for wet stretches in the summer and early fall in Colorado, even in the absence of a clearly-defined monsoon. With a La Niña most likely, we could loose out on the chance at a few strong surges of moisture this summer, and the overall intensity of the monsoon could be weaker and suppressed as a result.

While monsoon season could be slightly delayed in Colorado to the back-half of July, we’re only talking a few weeks at most. This of course doesn’t mean we will be completely dry in the Front Range in it’s absence. Our weather for the upcoming holiday weekend will offer daily chances of thunderstorms, even fairly good chances on July 4th. While this may seem “monsoon-like” on the surface, don’t be fooled! Wait until you see the triple digit heat wave Mother Nature may be planning for us next week 🔥🌡️😈!

Help support our team of Front Range weather bloggers by joining BoulderCAST Premium. We talk Boulder and Denver weather every single day. Sign up now to get access to our daily forecast discussions each morning, complete six-day skiing and hiking forecasts powered by machine learning, first-class access to all our Colorado-centric high-resolution weather graphics, bonus storm updates and much more! Or not, we just appreciate your readership!

.

Subscribe to receive email notifications for BoulderCAST updates:

We respect your privacy. You can unsubscribe at any time.

.

Share this Colorado weather update:

.