There’s no doubt about it. The La Niña pattern that developed late last summer is now dead. There’s no need to mourn this loss as this is actually good for Colorado and bodes well for a more active monsoon season this summer…or does it? Let’s take a look at the current state of ENSO and the weather outlook for the coming months.

Key Highlights from This Post:

- La Niña has ended in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean and ENSO-Neutral conditions are expected to stick around through the upcoming summer

- General data suggests that this recent weakening of La Niña is good news for Colorado as La Niña tends to suppress the monsoon in Colorado

- However, targeted historical analogs show a dry and warm summer is still favored for the Front Range and Boulder

- Long-range forecasts also indicate a dry and warm summer 2021 for our region

- A disastrous fire season is expected this summer and fall for Colorado as a whole

Help support our team of Front Range weather bloggers by joining BoulderCAST Premium. We talk Boulder and Denver weather every single day. Sign up now to get access to our daily forecast discussions each morning, complete six-day skiing and hiking forecasts powered by machine learning, first-class access to all our Colorado-centric high-resolution weather graphics, bonus storm updates and much more! Or not, we just appreciate your readership!

W

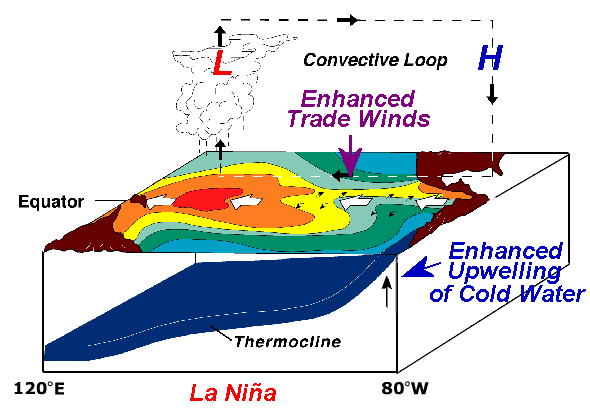

e begin with a reminder that La Niña is associated with cooler than normal ocean temperatures in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean, with enhanced easterly trade winds along the Equator and a shift of the warmest waters westward in the Pacific towards Polynesia.

Large-scale upward motion in the atmosphere and the resulting thunderstorm development along the Equator follow the warm pool in ocean water westward. This creates a convective loop across the expansive Pacific Ocean from west to east (shown above). These are just the localized effects of La Niña. Our atmosphere and ocean are intimately coupled on a global scale. This altered circulation in the Pacific thus leads to locations all around the world, including Colorado, being influenced by ENSO.

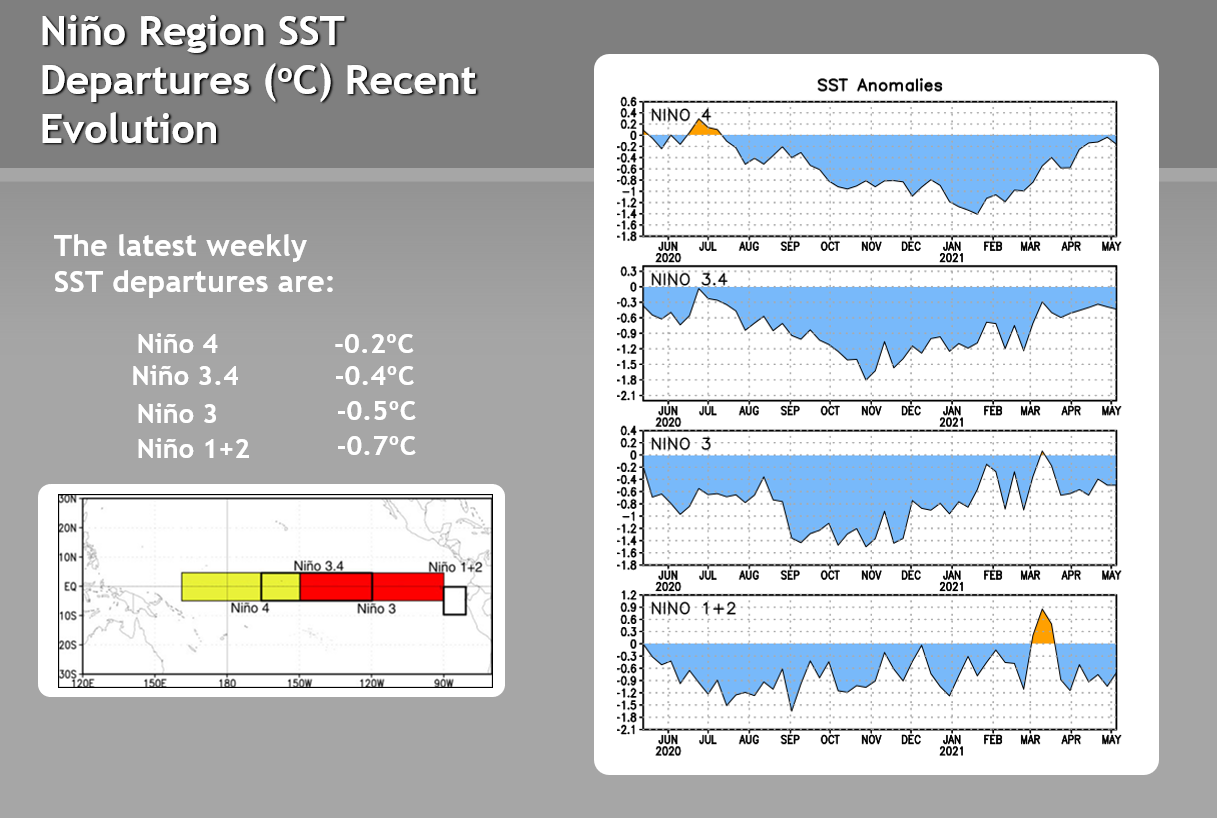

We knew it was coming, but the La Niña pattern which emerged during the summer of 2020 is now officially dead. The cold sea surface temperature anomalies in the Pacific Ocean have weakened considerably in the last month or two. Notice in the plots below how the cold anomalies have waned in the various regions of the Equatorial Pacific. Niño 3.4 is the one most often used for determining the state of La Niña, which is defined as a value of -0.5°C or lower. In this case, we see that Niño Region 3.4 warmed above this threshold back in early April.

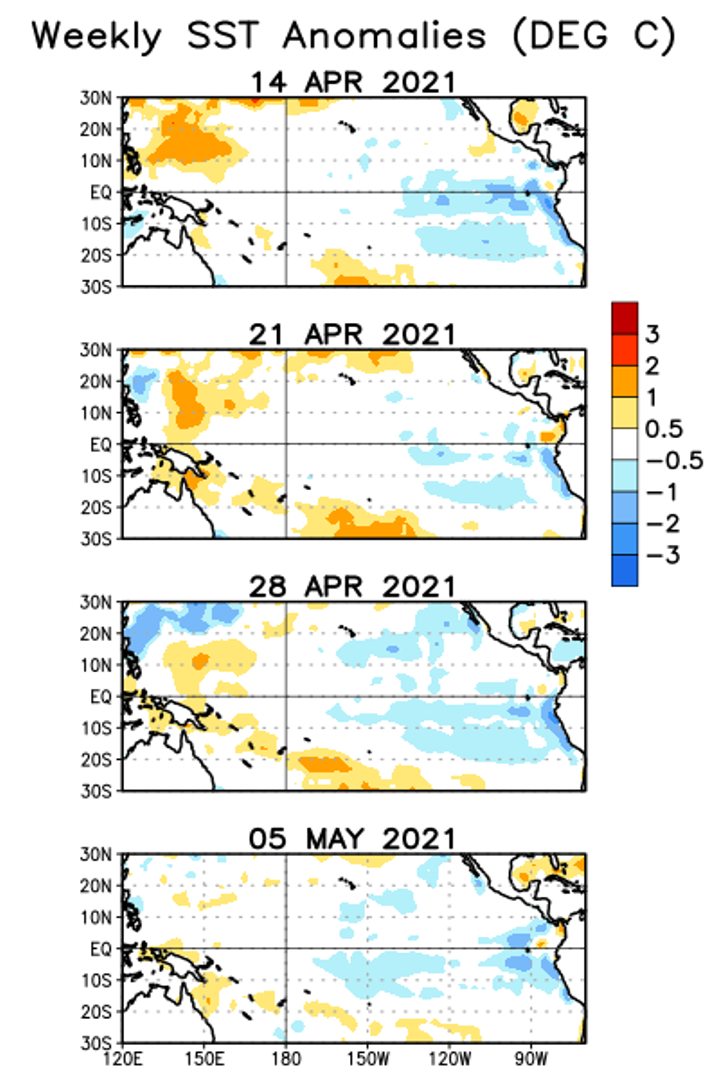

Looking at the evolution of sea surface temperature anomalies over the last month across the Pacific, not much has changed, just an overall slight dissipation of the cooler anomalies. That more or less agrees with the time series graphs above.

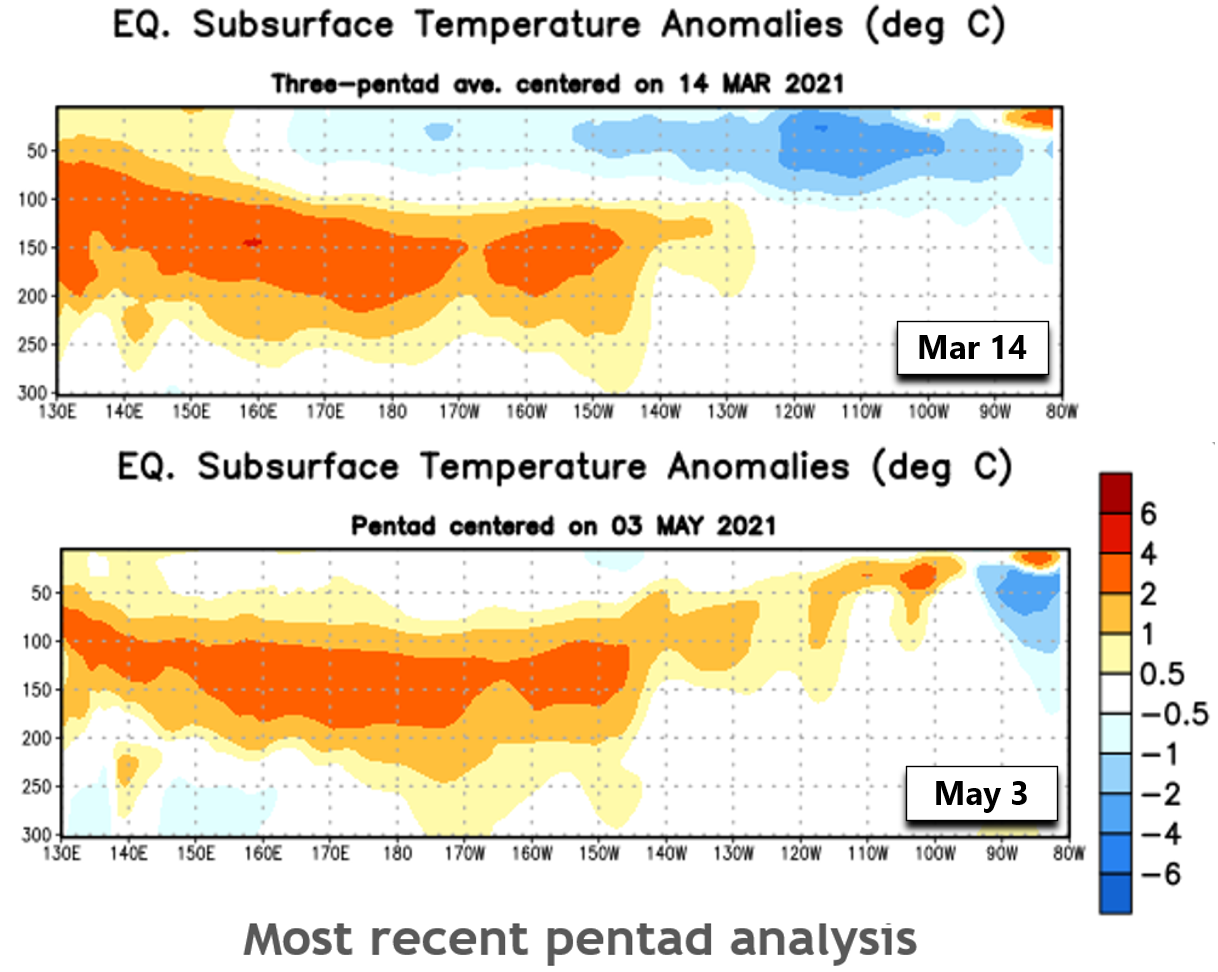

Sea surface temperatures, however, only tell part of the story, since they are just that, a surface reading. What’s going on beneath the surface can tell us a lot about the health of a current La Niña or El Niño pattern, and what lies ahead in its evolution. The diagrams below show ocean temperature anomalies below the surface. The y-axis is ocean depth from the surface at the top down to the 300 meters at the bottom. The x-axis is longitude, spanning from near Indonesia on the far left towards South America on the far right. Basically these are vertical slices of the Pacific Ocean along the Equator. Notice that back on March 14th, the cold La Niña signal was present most of the way across the Pacific, but only 50 to 100 meters deep. Also note that below the surface a very warm tongue of water was present on March 14th. This pool of warm water has been propagating eastward well below the surface for many months now! The most recent observations from May 3rd show the surface cold anomaly has nearly vanished and the warm sub-surface water has spread almost to South America. This is the diagram that really tells us that the final nail in La Niña’s coffin has already been pounded in!

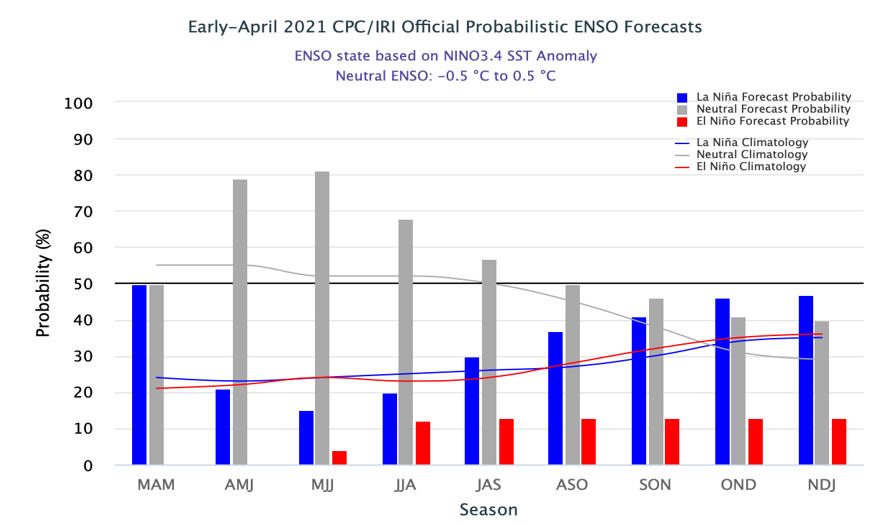

That’s enough of the hard science stuff for today! The key takeaway here is that La Niña is caput. We’ve now transitioned into an ENSO-Neutral phase and based on official forecasts, ENSO-Neutral is the most likely pattern to persist through the upcoming summer and most of autumn. However, La Niña is favored to return again later in 2021, but we’ll have to wait and see if that comes to fruition.

Nonetheless, La Niña taking a summer vacation is good news for the Front Range and most of Colorado. This is because the summer monsoon pattern is often suppressed further south during La Niña, whereas El Niño amplifies the reach of the monsoon into Colorado. Let’s walk through some data to confirm this.

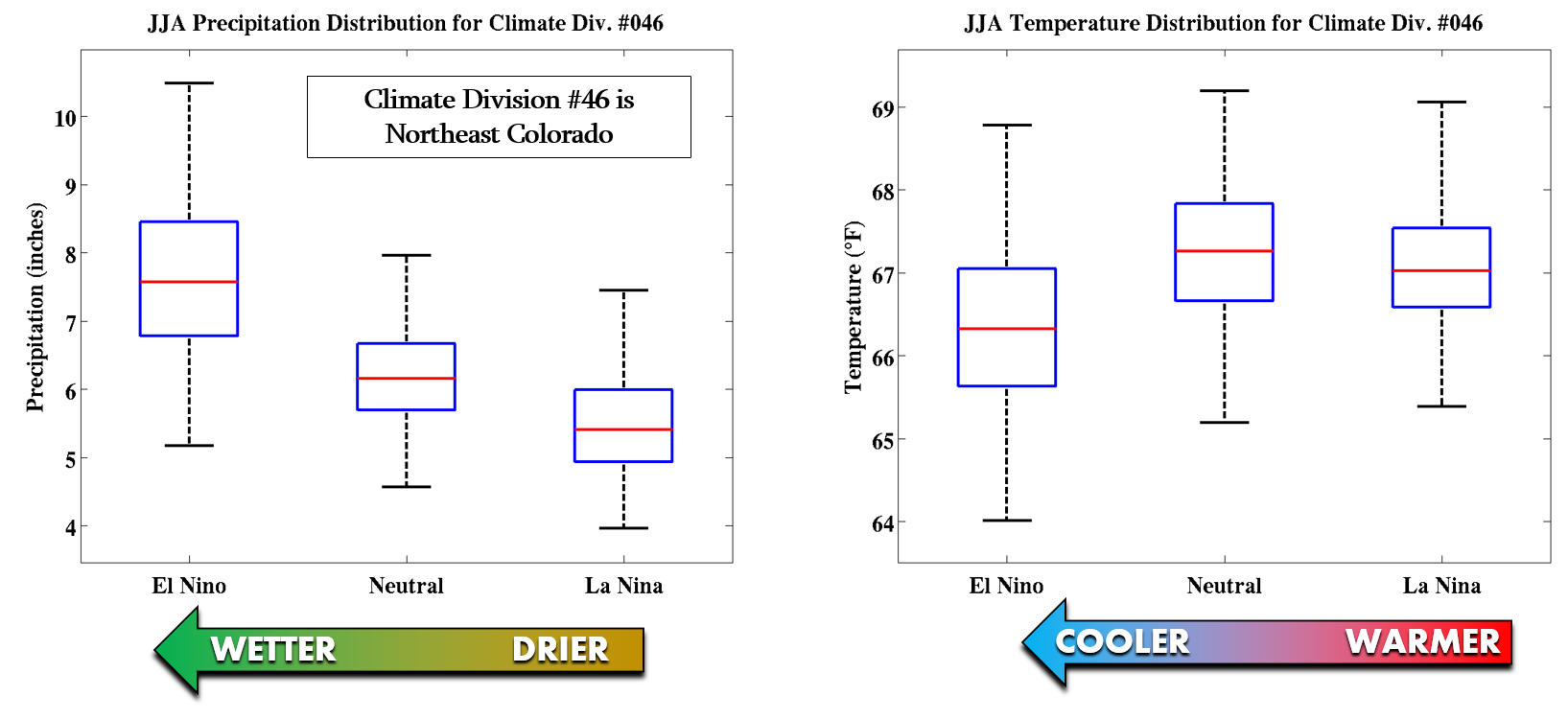

Shown below are box-and-whisker plots of precipitation (left) and temperature (right) for Climate Division #46 during the various phases of ENSO for the months of June, July and August (JJA). This is essentially the region comprising northeast Colorado and also some of north-central Colorado. A clear trend is evident from warmer and drier conditions during La Niña towards wetter and cooler conditions during El Niño. The shift in outcomes when going from La Niña to ENSO-Neutral, like we are right now, tells us that our area stands a better chance to see more precipitation and slightly warmer temperatures than if La Niña had persisted into the summer season.

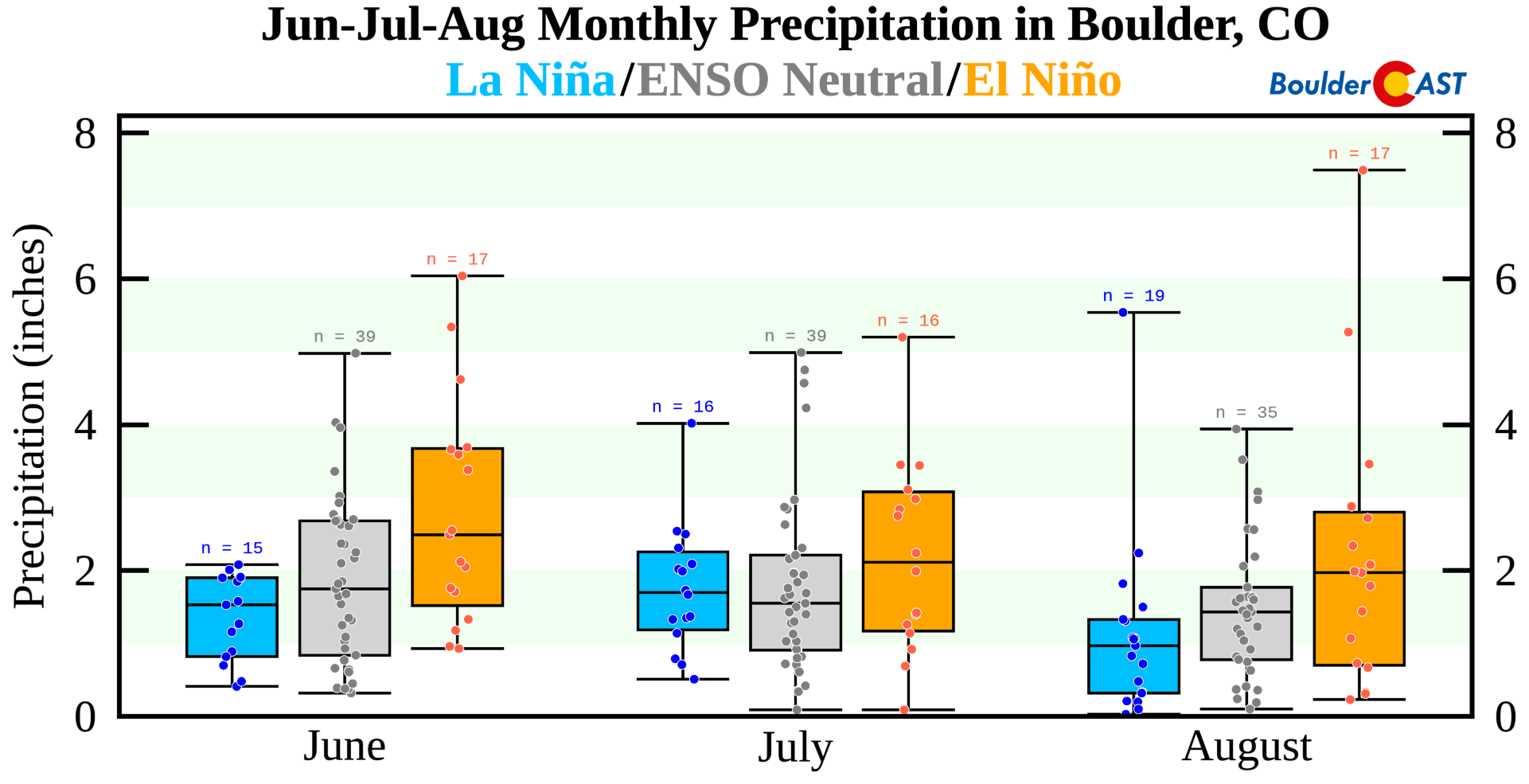

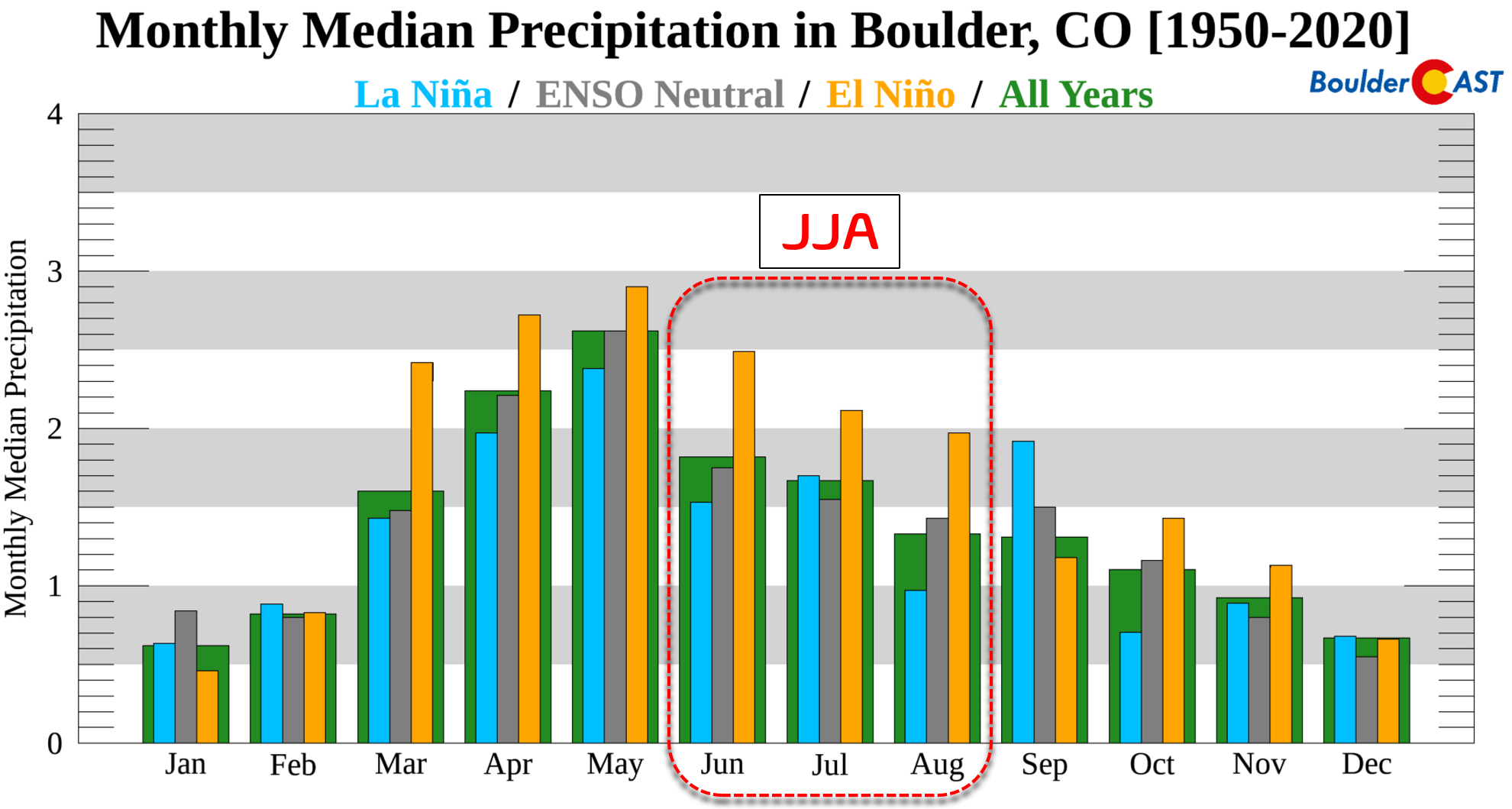

If we look at the historical data just for Boulder, we see the same trend in summer-time precipitation. June, July and August are all notably drier during La Niña compared to El Niño, and even compared to ENSO-Neutral conditions in June and August.

Total summer precipitation amounts decline nearly 40% during La Niña compared to El Niño. Here are the median precipitation amounts for JJA in Boulder:

- La Niña: 4.2″

- ENSO-Neutral: 4.8″

- El Niño: 6.6″

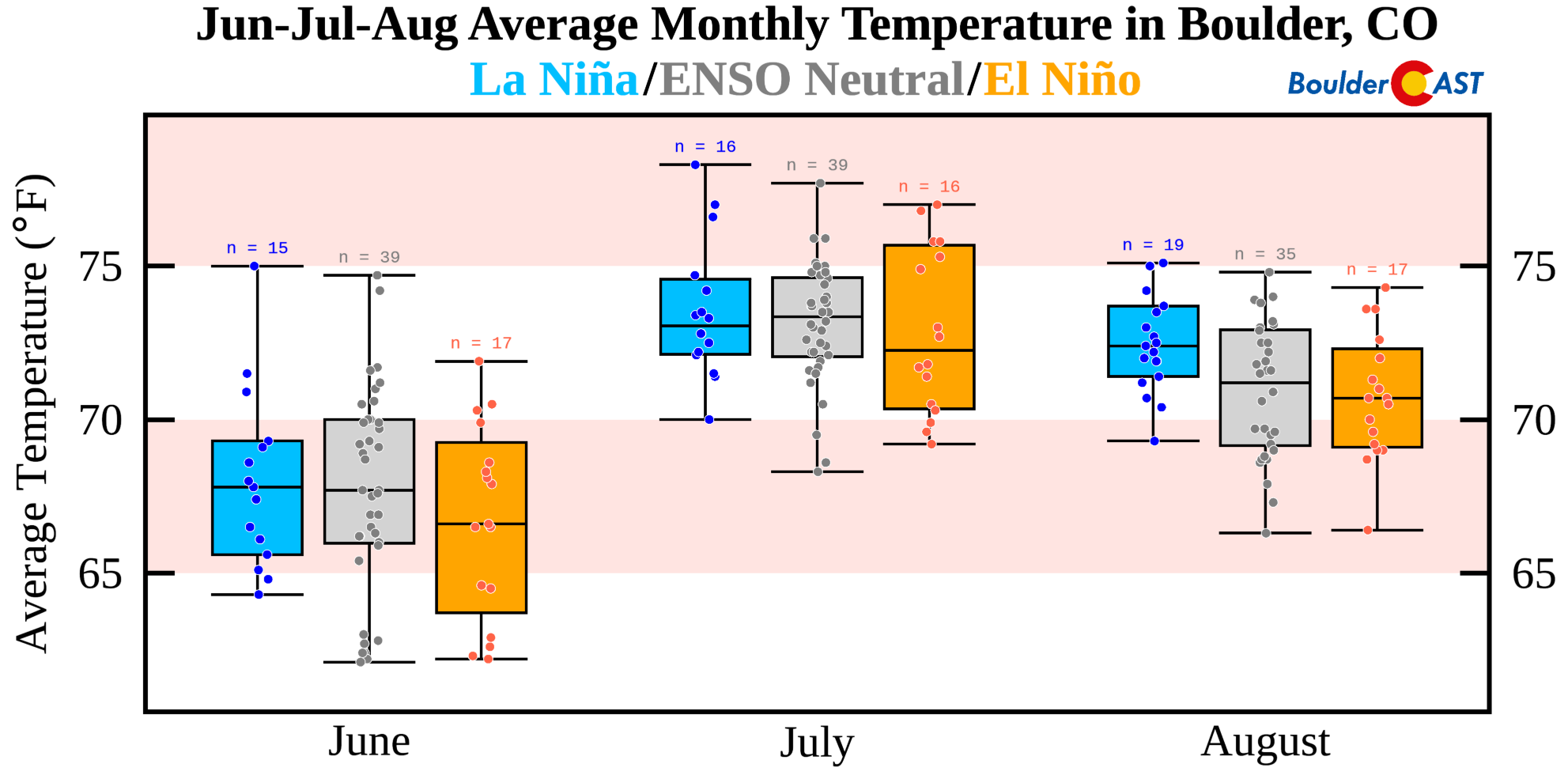

Shifting over to temperatures, we note the same trend in Boulder that we saw earlier for all of northeast Colorado. More frequent monsoon clouds and thunder showers during El Niño take the edge of the scorching summer heat so common in the High Plains of eastern Colorado. El Niño summers are notably colder by 2 to 3°F overall in Boulder. However, on average ENSO-Neutral summers have similar temperatures to La Niña summers.

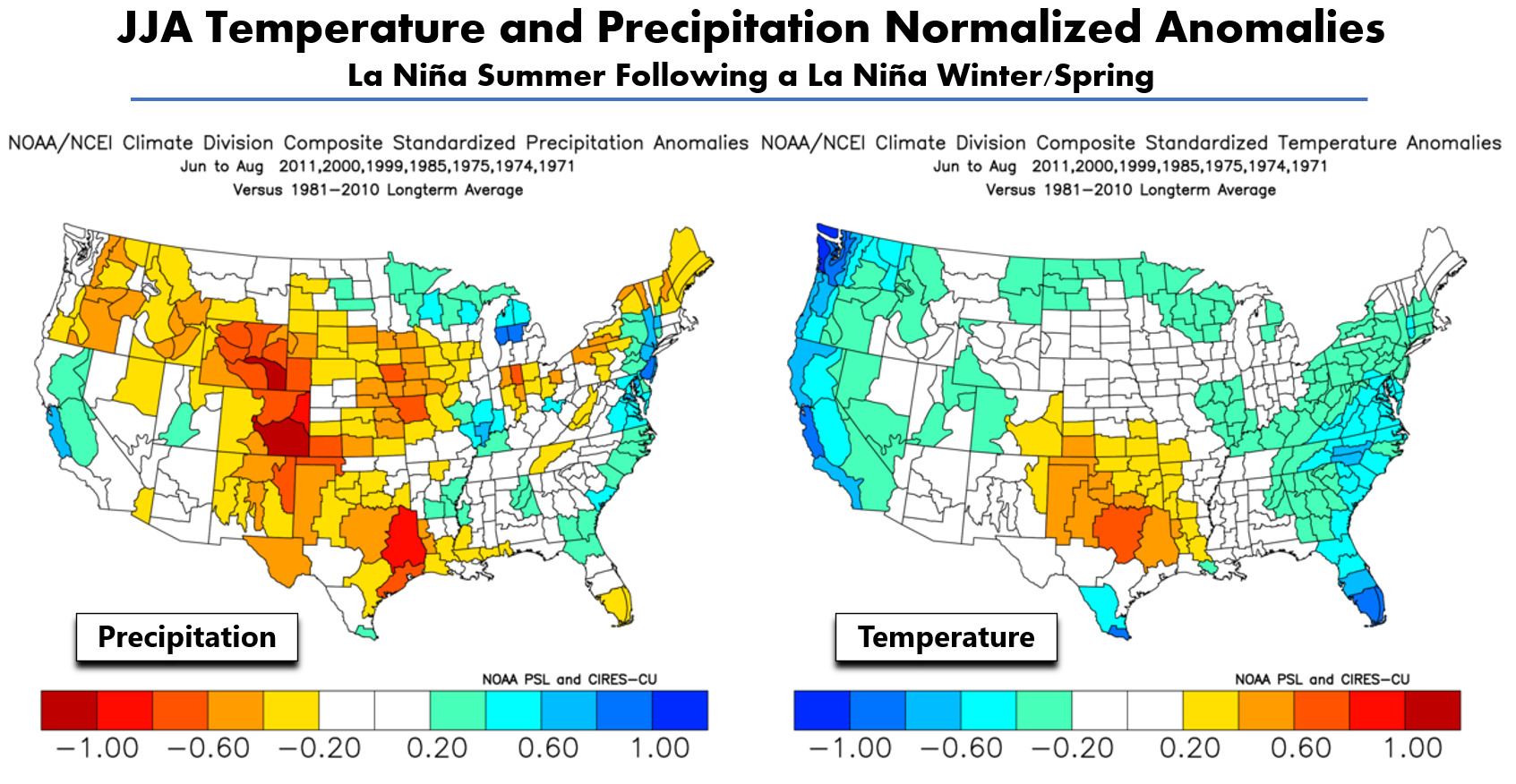

So far, looking at data generally pertaining to ENSO patterns, we would expect a slightly drier and warmer than normal summer. We can’t stop there though. Let’s take a quick check of the historical analog patterns relevant to the current situation. Shown below are summertime anomalies of precipitation (left) and temperature (right) for La Niña summers following a La Niña winter. These are the anomalies we might expect if La Niña were to persist through the upcoming summer. But as we discussed earlier, that’s not going to happen. In any case, we do see a dry signal for all of Colorado in addition to many other western states that also depend on the monsoon. Temperatures for northeast Colorado in this situation generally stick close to normal or slightly above.

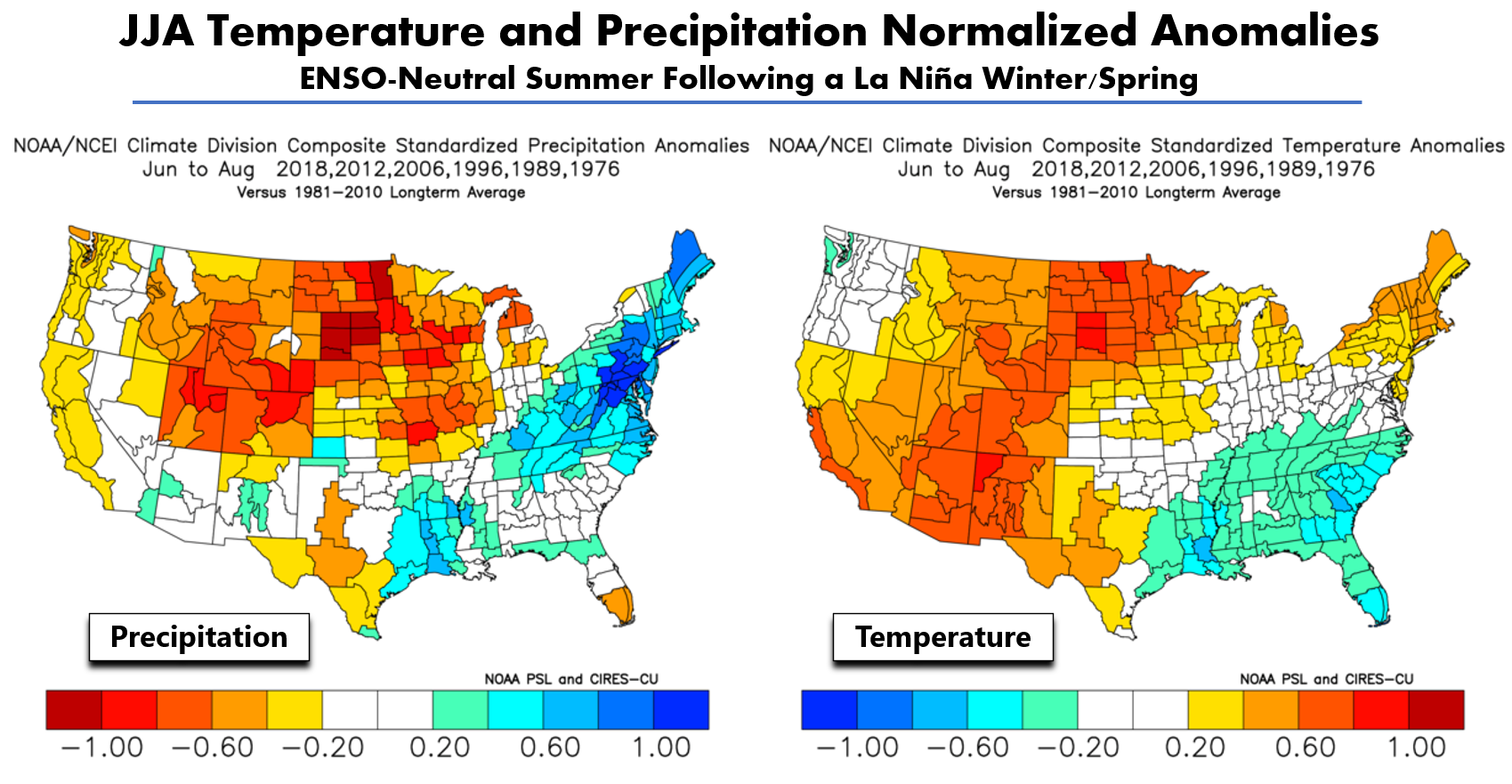

Now the most relevant analogs, those for an ENSO-Neutral summer following a La Niña winter and spring. This is the exact situation we are in right now. Based on six occurrences of this type of ENSO shift in the last 50 years, the outlook is not as favorable for Colorado. A strong warm and dry signal is indicated across the entire state. The most recent analogs for this situation are 2018 and 2012. Both of those summers were extremely warm and dry for Colorado. If you recall, 2018 had almost no monsoon season whatsoever. The same was true last year as well.

So far we have reviewed the outcomes from past summer seasons, and nothing more. Remember, as with most of weather, nothing is ever set in stone. ENSO is a global indicator that just gives us hints about conditions that are slightly more likely to occur. The “randomness” of Earth’s complicated weather patterns from year-to-year is much more dominant on our weather than ENSO could ever be!

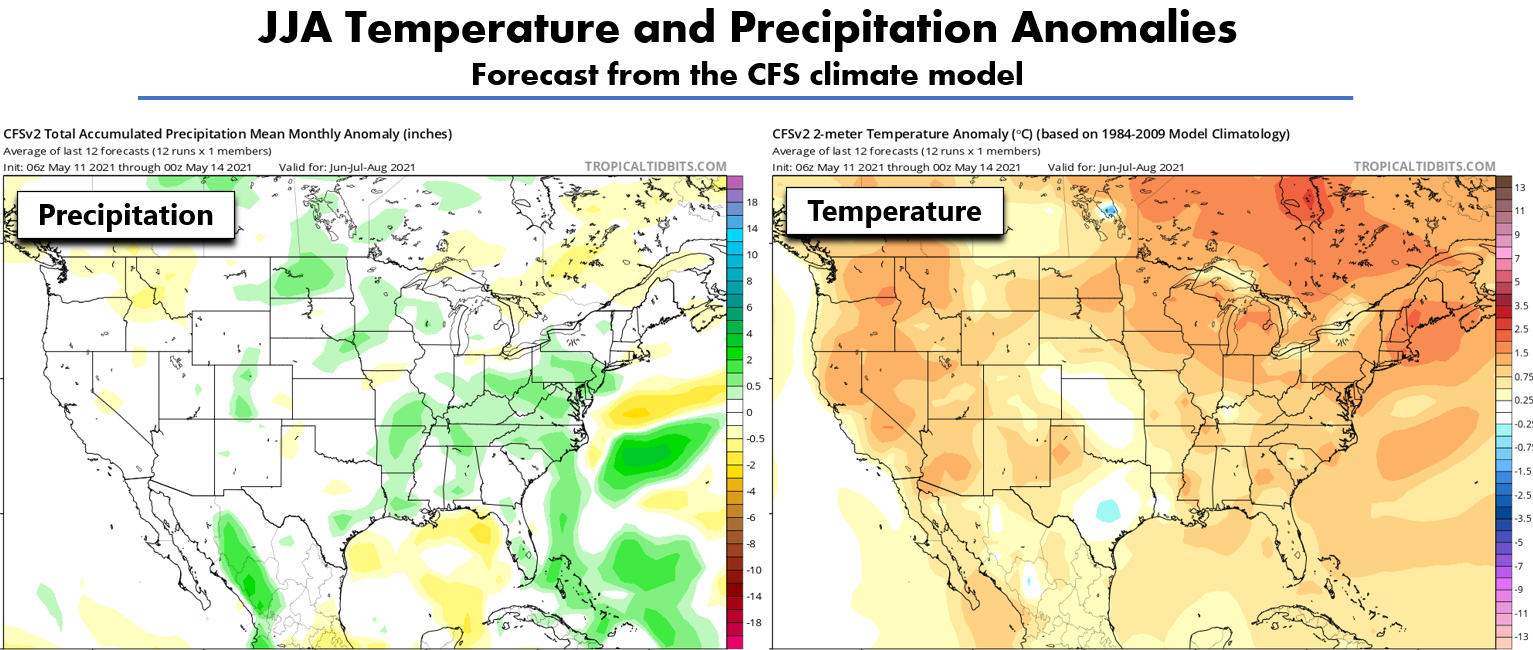

With that said, let’s take a look at actual forecasts. First, the prediction from a popular climate model, the CFS. This model is predicting a warm summer for most of North America (below right). Though interestingly at the moment, Kansas and eastern Colorado are showing some of the least positive anomalies leading to more or less a normal summer in terms of temperatures. For precipitation (below left), the CFS model is predicting a wet summer for the southeast US and Mid-Atlantic, which follows right along with the analogs we showed earlier. However, there is a prediction for above normal precipitation in the central mountains of Colorado. A closer inspection of the model data shows a forecast for a particularly wet July and August in this area. This doesn’t really make sense to us, as the primary mechanism for summertime precipitation in our state’s High Country is the monsoon, which we aren’t expecting to impress this year.

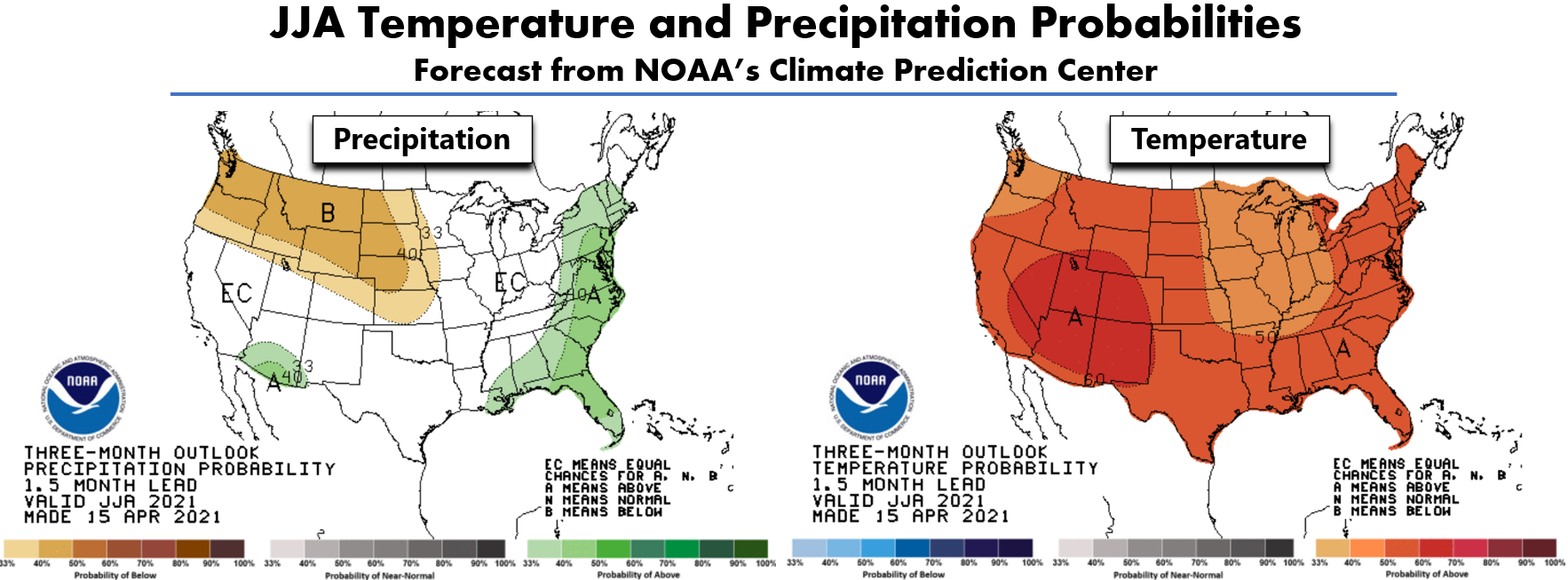

Below is the latest summer forecast from the Climate Prediction Center. They are predicting elevated chances of a dry summer in Pacific Northwest and northern Rockies, including Front Range Colorado, as well as increased chances for warmer than normal temperatures for the entire continental United States. Wet weather is favored in the Southeast and along the East Coast, as well as in extreme southern Arizona where monsoon season is actually more intense during La Niña and ENSO-Neutral conditions. Overall, their forecast matches well with the CFS model solutions, the situational analogs we showed earlier, and our general thinking about how the summer will play out as a whole.

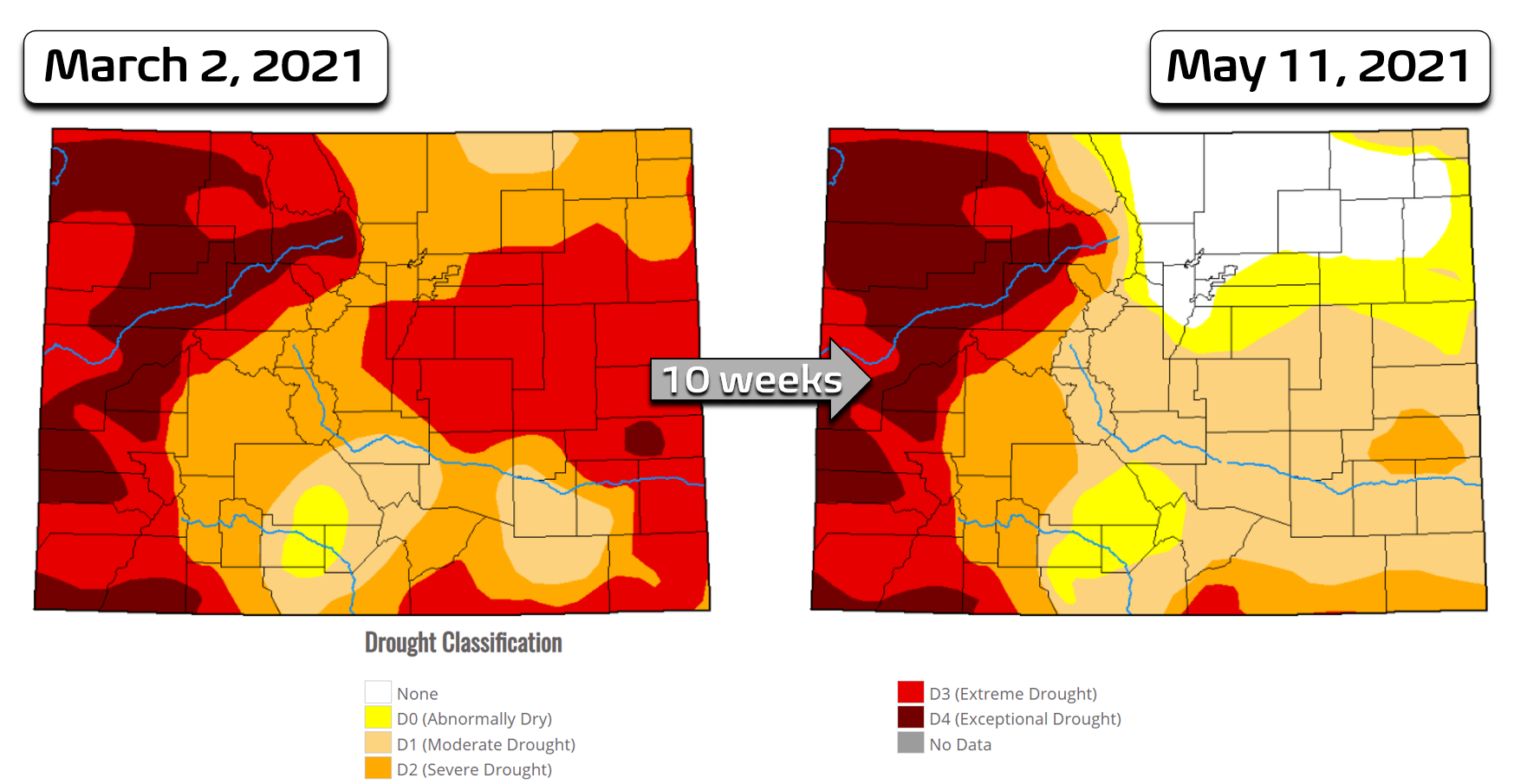

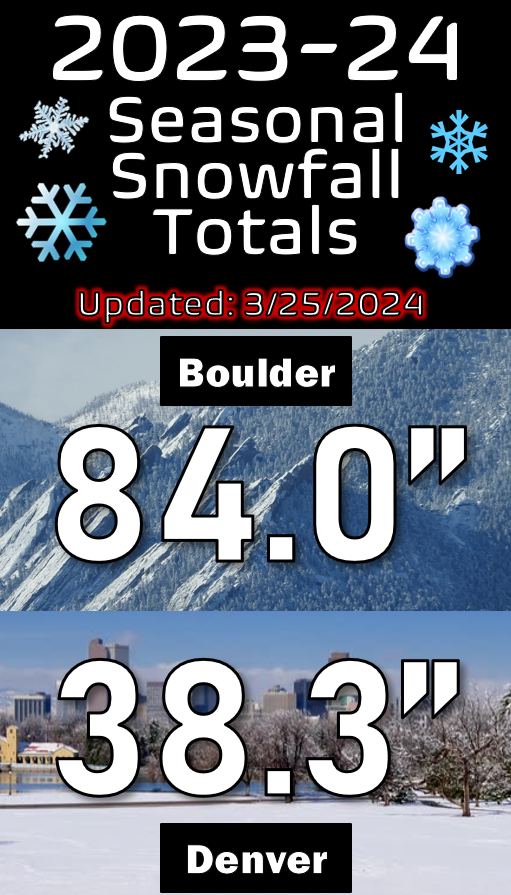

There has been a lot of positivity around the improving drought the last few months beginning with the epic snowstorm in mid-March. The rapid improvement in the drought around Denver and Boulder is incredible, but let’s not get ahead of ourselves. It’s not all good news. Since mid-March, it’s true that we’ve seen a complete eradication of drought from Denver to Cheyenne and areas eastward. However, southern and particularly western Colorado remain deeply entrenched in crippling drought. Unfortunately these are the areas most susceptible to wildfires.

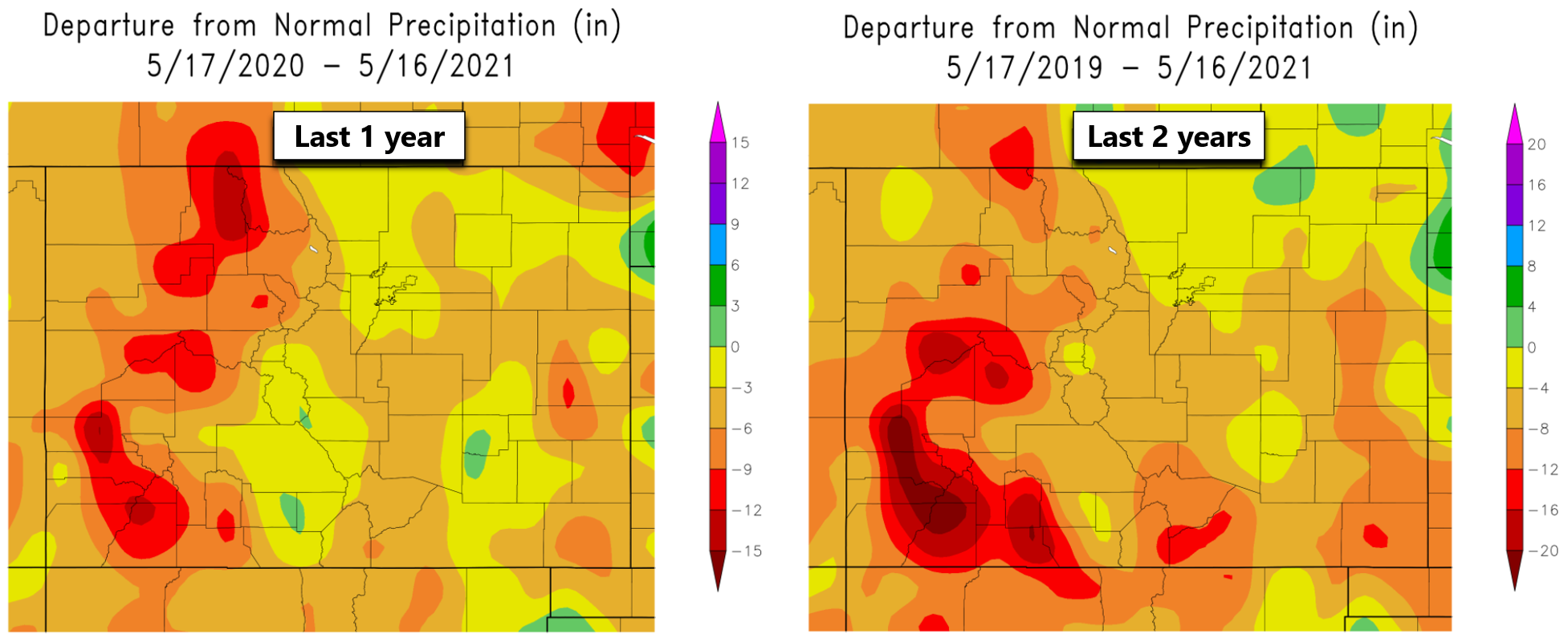

Furthermore, though technically drought is not active in the immediate Front Range area right now, we’re still running a long-term precipitation deficit over the last year (below left) and two years (below right). The deficit is only a few inches, but that doesn’t matter. This long-term precipitation shortage makes it much easier for our region to slip back into drought if the summer months ahead are dry, which as we’ve already discussed, is the favored outcome right now.

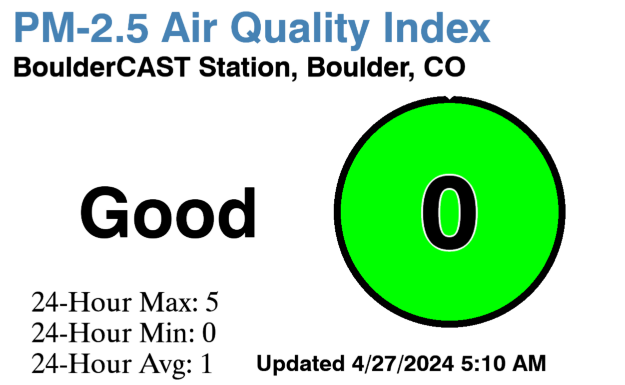

We’re not going to sugarcoat potential impacts. The summer months ahead will be fiery for much of Colorado and the western United States as a whole where drought continues to rage. Even if the wildfires are distant to the Front Range, the air quality impacts could be drastic as we saw last summer and years prior. The situation isn’t entirely out of our hands, though. A vast majority of wildfires are human-caused and ongoing fire bans will help mitigate some (but not all) of the idiocy this summer. The somewhat lessened monsoon season we anticipate may actually help things along as well by reducing the chance of cloud-to-ground lightning igniting fires in areas with extremely dry vegetation. We urge everyone to use extreme caution in the many months ahead and follow the local fire guidelines of whatever drought-stricken area you may end up in. Getting through the potentially dry summer season with as little damage as possible and hoping for a wet autumn/winter ahead is sadly the best case scenario for Colorado right now.

Stay up to date with Colorado weather and get notified of our latest forecasts and storm updates:

We respect your privacy. You can unsubscribe at any time.

Help support our team of Front Range weather bloggers by joining BoulderCAST Premium. We talk Boulder and Denver weather every single day. Sign up now to get access to our daily forecast discussions each morning, complete six-day skiing and hiking forecasts powered by machine learning, first-class access to all our Colorado-centric high-resolution weather graphics, bonus storm updates and much more! Or not, we just appreciate your readership!

.