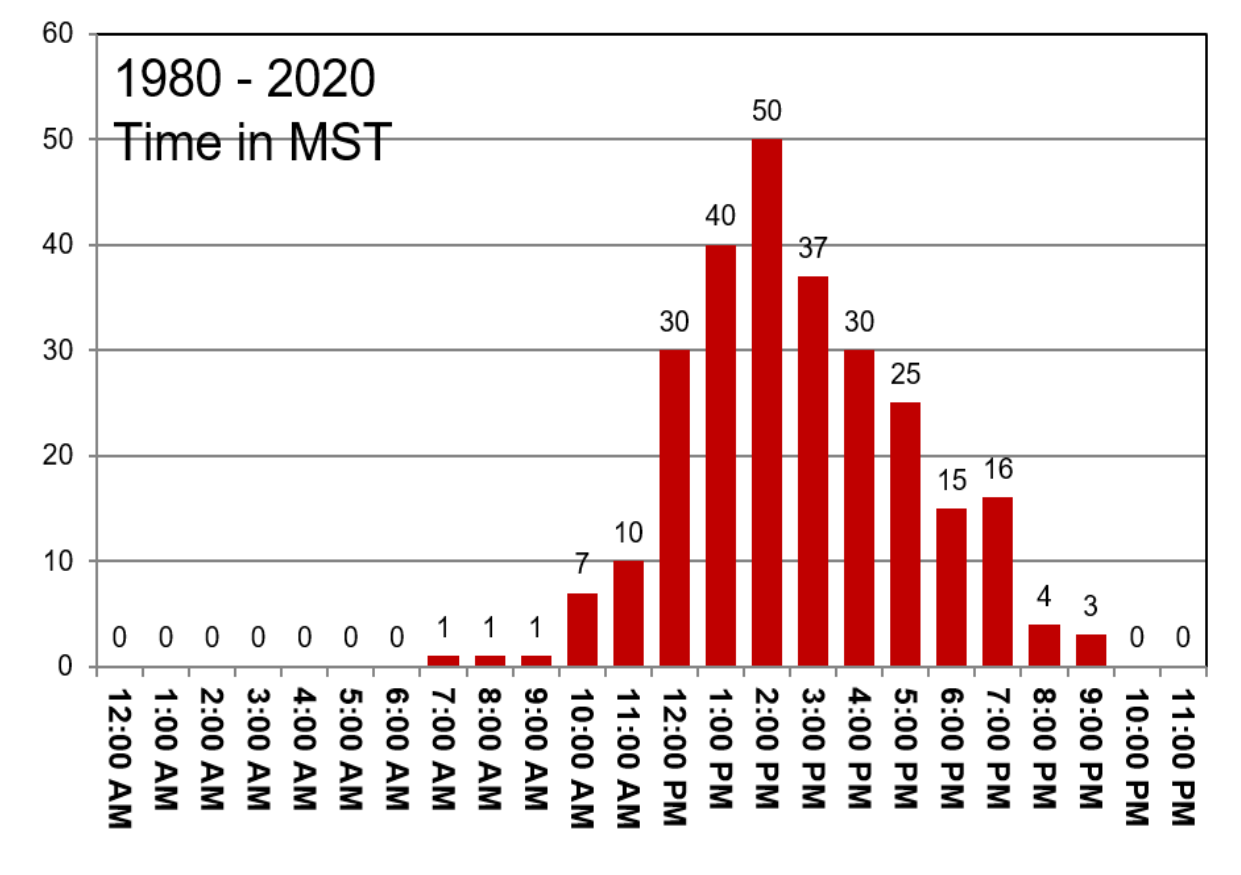

As you know, thunderstorms are usually a staple of summer in Colorado! Almost every day, monsoon moisture boils up into dark early afternoon clouds, some of which produce deadly cloud-to-ground lightning. We briefly review a few statistics and remind you that Colorado is ranked near the top of the list for lightning-related fatalities for a reason.

Weather forecasting and public awareness have decreased annual lightning fatalities by 95% since 1950. A remarkable accomplishment that meteorologists often use to toot their own horn. Of course, advances in technology since then mid-20th century greatly reduced the amount of people regularly working outdoors (i.e. farming). Undeniably this was a major reason for this decline as well.

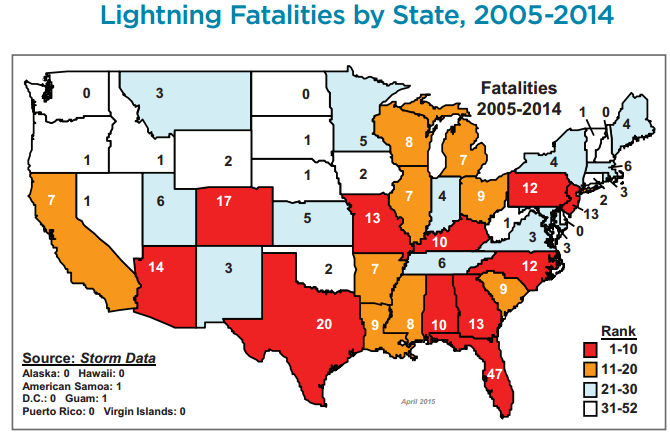

Even still, over the last decade, around 30 people per year are killed by lightning in the United States, with Colorado being one of the most deadly states. The map below shows the number of lightning fatalities per state during the decade ending in 2014. Colorado trailed only Texas and Florida in deaths during this time-frame.

Source: Vaisala

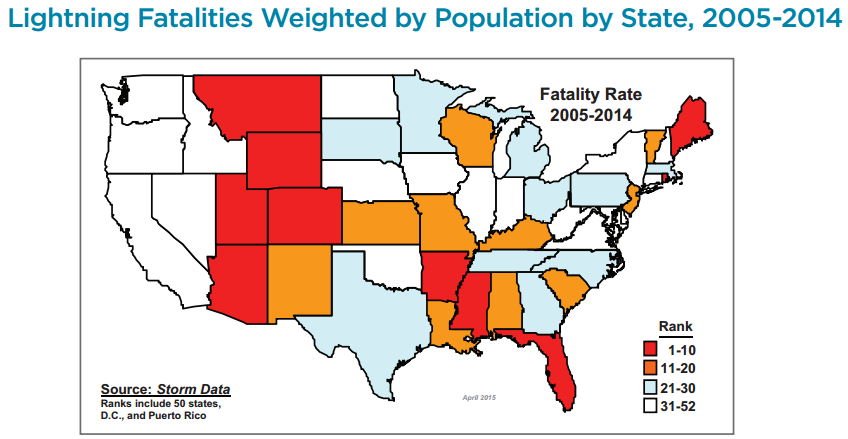

However, when you consider that Texas and Florida have at least four times the number of people, the Centennial State leap frogs them both in lightning deaths weighted by population. In fact, many less-inhabited Rocky Mountain states jump to the top of the list. This is the map that shows which states people are statistically most likely to perish from lightning.

Source: Vaisala

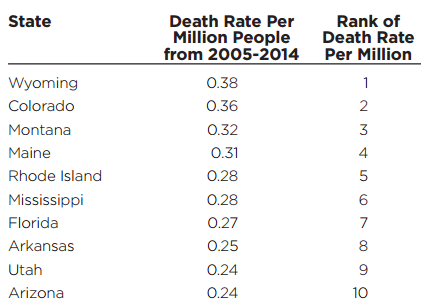

Here are the detailed numbers for those red states above. Colorado rests in second place, just behind Wyoming and just ahead of Montana.

Source: Vaisala

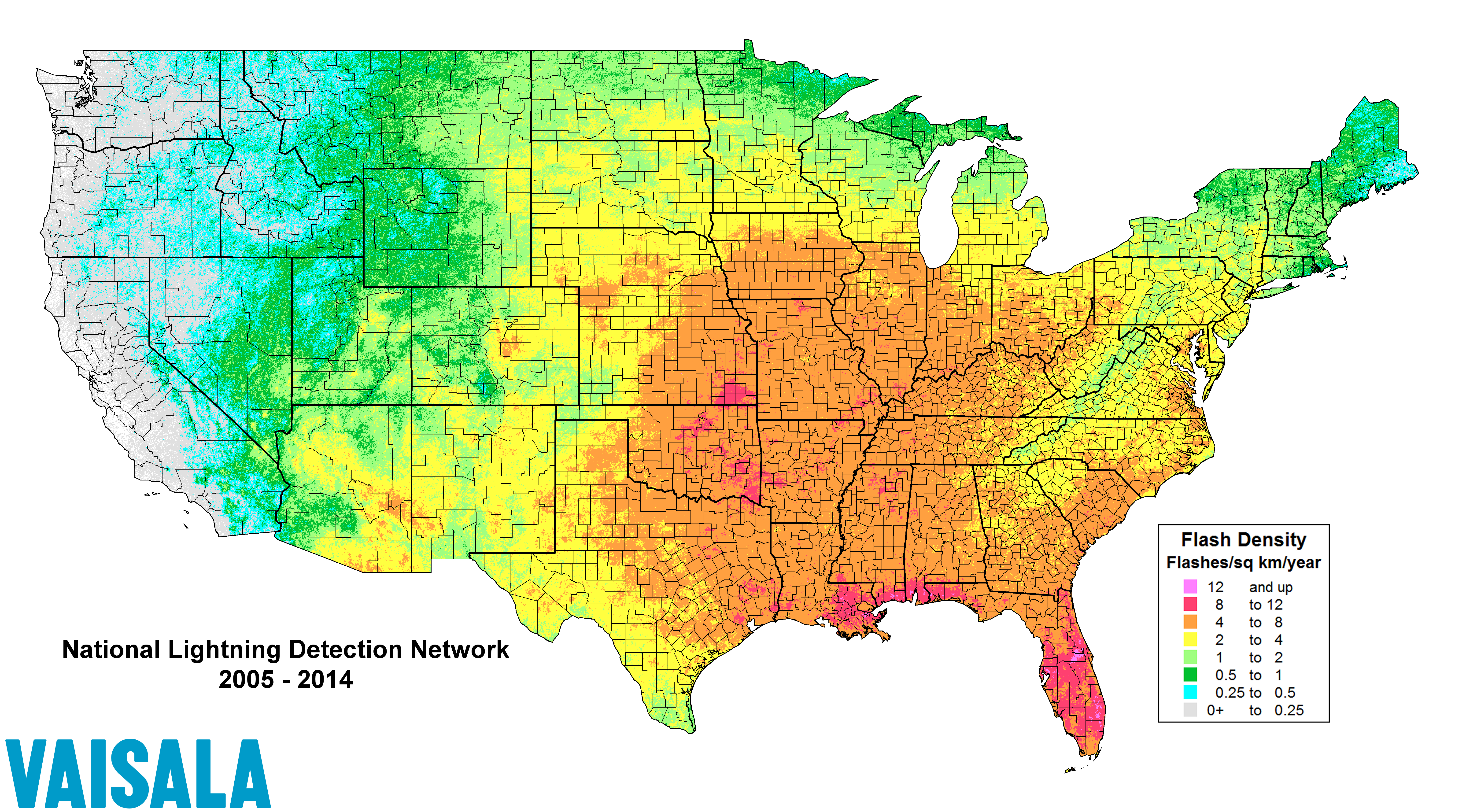

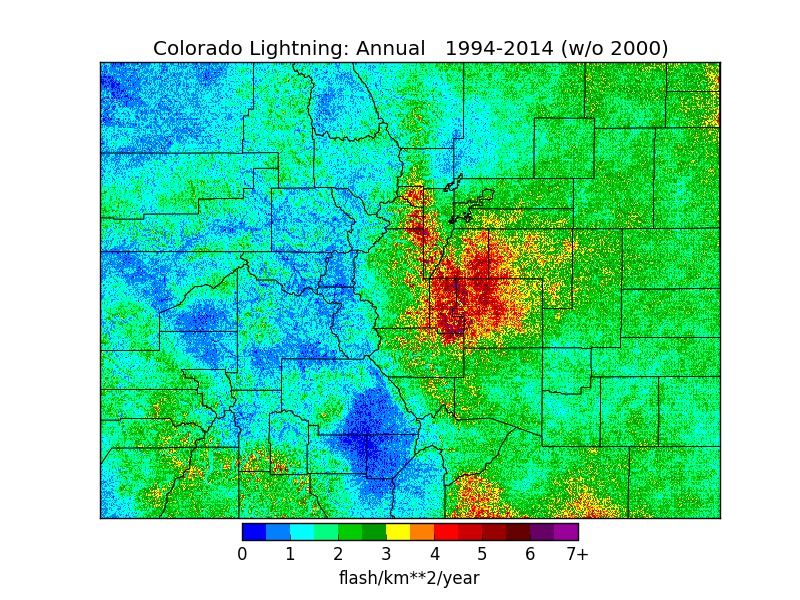

So what makes the northern Rockies, including Colorado, such a statistically deadly place for lightning? We can tell you one thing, it’s not the shear number of lightning strikes! Our state actually sees an average amount of lightning compared to the rest of the country…about two strikes per square kilometer per year. This is a hard unit to conceptualize. However, it’s roughly a count on the amount of strikes per year that are close enough to shake your entire house and make you jump. In Denver and Boulder, this is TWO. In the stormiest parts of Florida, it’s TWELVE!

Source: Vaisala

Now let’s take a closer look at Colorado’s lightning counts. We see a general minimum in lightning over eastern Boulder County, around one strike per square kilometer. A huge maximum is visible along the Palmer Divide south of Denver, where up to 6 strikes per square kilometer are observed per year.

Source: National Weather Service, Pueblo Office

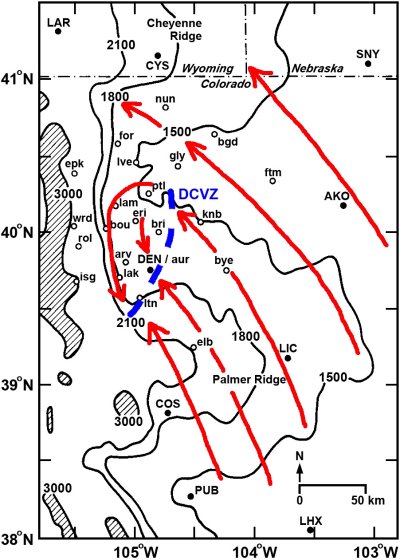

The cause for this spatial distribution is tied to a low-level, topographically-forced wind circulation known as the Denver Cyclone. This wind pattern occurs in Denver about 1 out of every 3 summer days. It facilitates convergence (lift) and feeds moisture to support the storms over the Palmer Divide much of the summer. This resulting convergence can also be an ignition point for severe thunderstorms around the Metro area. We’ll have to cover this localized weather phenomenon in more detail in another post. It’s really quite fascinating!

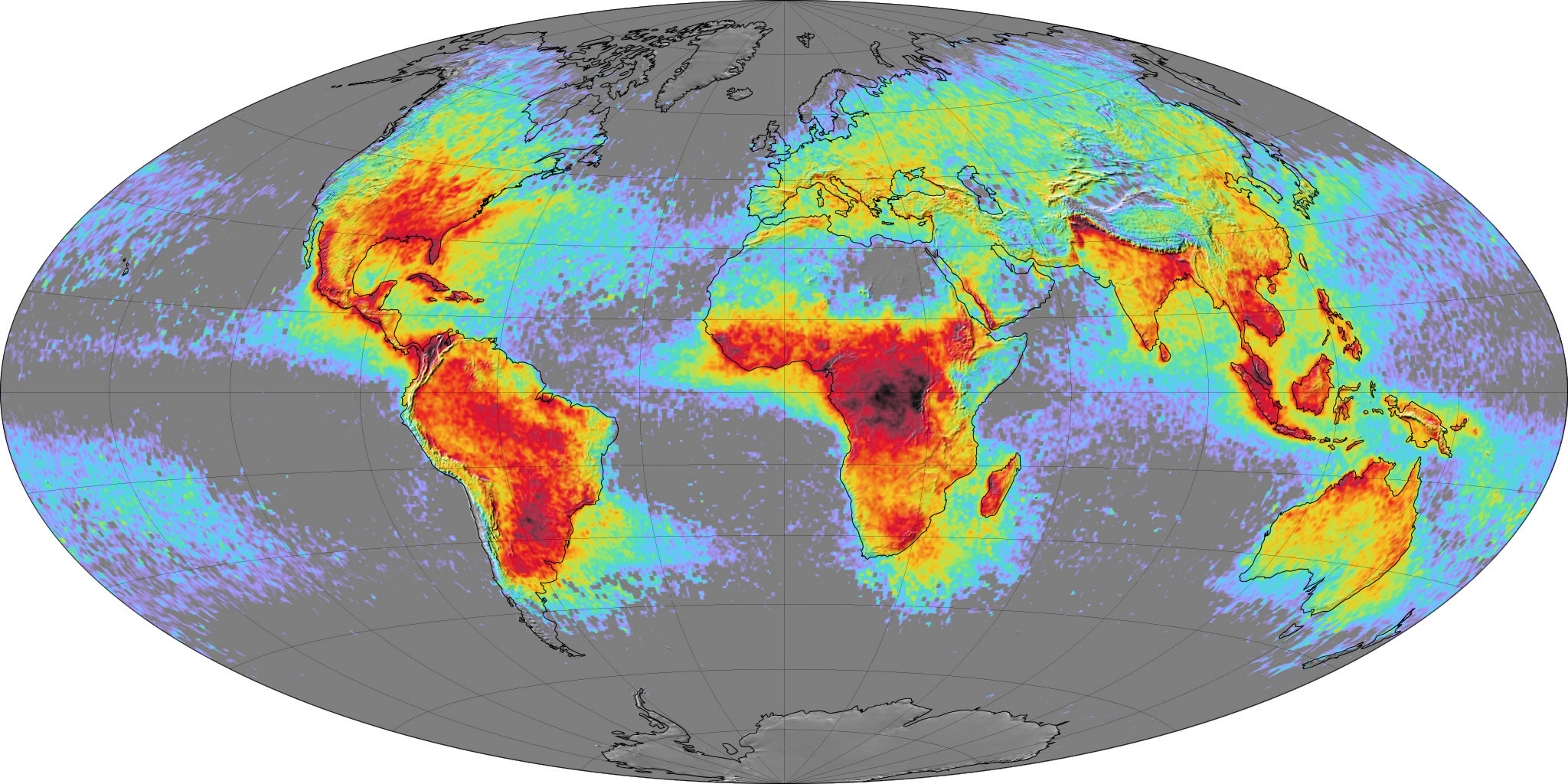

Looking bigger picture, keep in mind that other places around the world have MUCH higher counts of lightning than the United States. No where can compete with the rain forests of south central Africa….

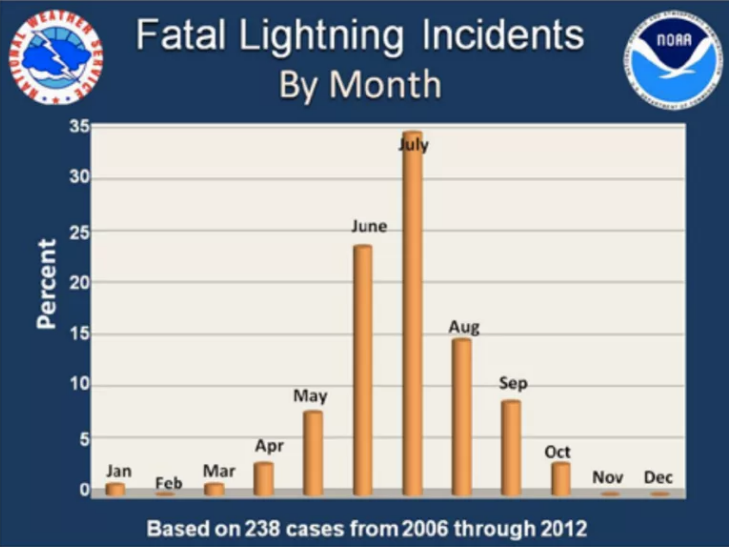

If not the amount of lightning, is it the type of lightning that leads to Colorado’s elevated death rate? To some degree…yes. A bulk of our lightning occurs during the summer monsoon season, which runs June through August. This annual maximum holds true for most of the country actually.

Source: NOAA NWS

Because of the dry air near ground-level and the rugged terrain, thunderstorms here are often high-based, meaning the actual cloud itself is higher above ground. These type of storms, called “dry thunderstorms”, have all the lightning of a normal storm, but with much less rainfall actually reaching the surface. Even with all our lightning awareness, if torrential rainfall isn’t impeding, many folks are less likely to take shelter as a storm approaches…especially in Colorado where monsoon thunderstorms move out as quickly as they arrive. Heck, why take shelter if you’re not even going to get wet? You literally only have a one-in-a-million chance of getting struck by lightning.

Fun fact: Approximately 85% of all lightning deaths in the United States are men. Apparently men are either bigger risk-takers, outdoors more at the wrong times, or slower to react and take shelter when lightning strikes.

Another big contributor to the elevated death rate in the Rocky Mountain states is the lack of consistent lightning shelter and the outdoor enthusiasm adorned by the population. Peak lightning season overlaps perfectly with the alpine hiking and backcountry season here in Colorado. Let’s face it…there’s not a lot of viable lightning shelter on the summit of Longs Peak or in your tiny tent in a forest of evergreens. Anytime you partake in these type activities during the summer months, it’s ALWAYS a bit of a gamble.

Do your best to stay alert to changing weather conditions and try to identify lightning-safe (or safer) areas ahead of time. And of course, there is always the option to stay indoors when lightning threatens, but that’s no fun!

Head over to the National Weather Service’s Lightning Page for more lightning tidbits, safety tips, casualty data, and other related resources.

.