This week NOAA announced that the GOES-17 weather satellite has passed its final examination! It now operational as GOES-West at an orbital position of 137.2°W longitude…basically in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. We discuss how this new data will benefit our weather forecasts, the status of the catastrophic hardware issue discovered post-launch, and the type of stunning imagery we can look forward to for years to come.

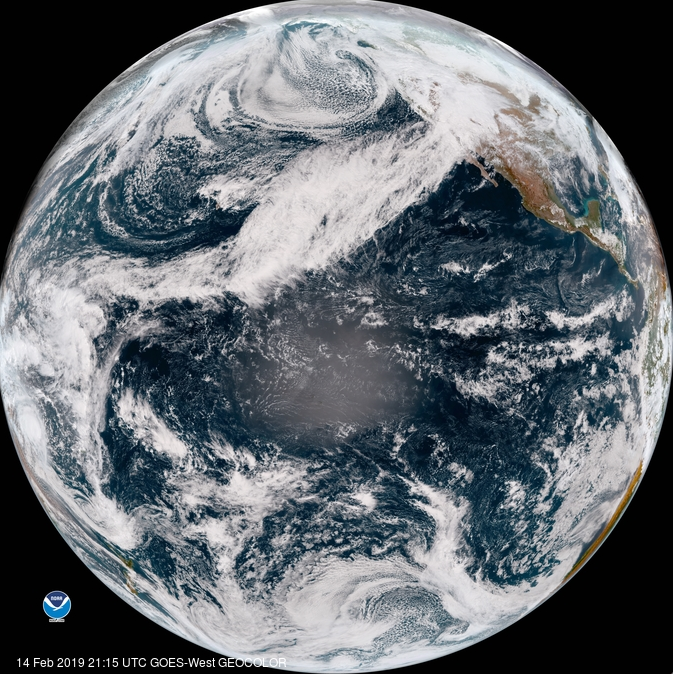

All GOES satellites are geostationary. That is, their orbital speed exactly matches the rotational speed of the Earth such that they always capture the exact same view of planet. The image below shows the satellite’s “full disk” view of Earth from Thursday afternoon. It had a marvelous birds-eye look of the atmospheric river we have been discussing all week!

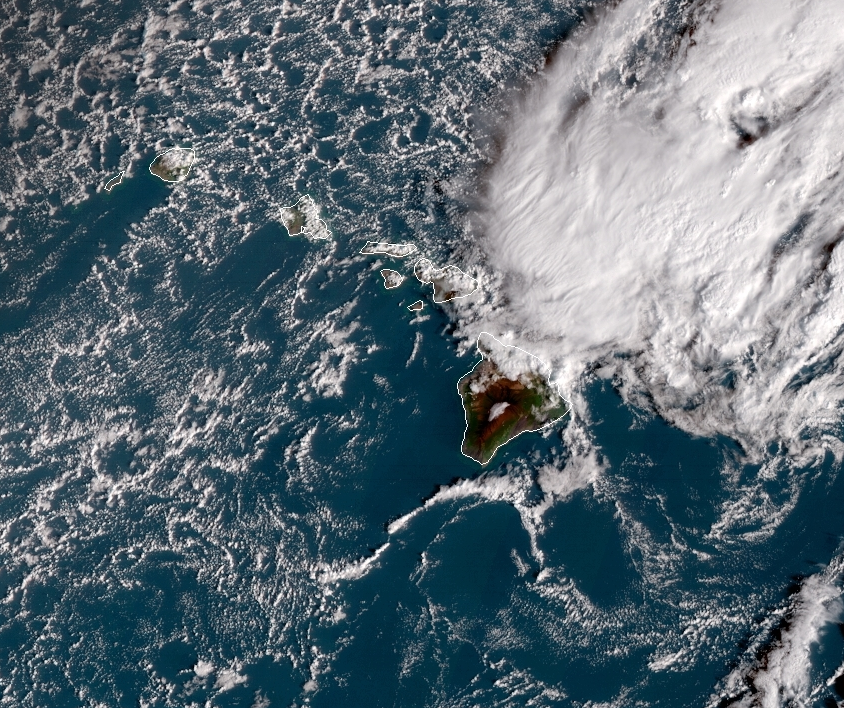

The full-disk picture is great, but as you know, the next-generation GOES satellites really shine at smaller scales where their high resolution sensors can be put to good use. The true color image below is a zoom-in on Hawaii from the full-disk image above. Look at those glorious details!

As meteorologists here in Colorado, we’re most excited about GOES-17 because it gives us a much more detailed look at storm systems as they progress across the Pacific Ocean. As you know, most of our large-scale weathe-makers arrive to us from that direction. Here is an example of one such storm system coming ashore into California about two weeks ago:

GOES-West true-color animation near California on February 2, 2019.

Below is another animation of clouds forming in the vicinity of the Big Island in Hawaii from about one month ago. This demonstrates the stellar spatial and temporal resolution of GOES-17.

GOES-West true-color animation of the Big Island of Hawaii from January 15, 2019.

For detailed satellite imagery of the local Denver Metro area, GOES-West is actually at a slight disadvantage to GOES-East. This is because GOES-West is about 7% further away from us than GOES-East. Regardless, the quality and quantity of the new data available far exceeds anything we’ve ever had before.

Graphic showing the view extents of GOES-East and GOES-West and the location of Denver | Source: NOAA

Of course, visible satellite imagery is only one small portion of what the next-generation GOES satellites offer. The on-board imager is equipped to handle 16 different wavelength bands ranging from 0.47 to 16 microns. With all of these bands, either by themselves or when combined together, lots of additional information can be gleaned, such as:

- Tracking volcanic ash and wildfire smoke plumes

- Monitor low, mid, and upper-level moisture

- Measure the temperature of the air

- Easily distinguish clouds from snow cover

- Determine if a cloud is comprised of water droplets or ice crystals

- Measure atmospheric ozone concentrations

Head over to the GOES website for some handy info-graphics covering each of the 16 bands.

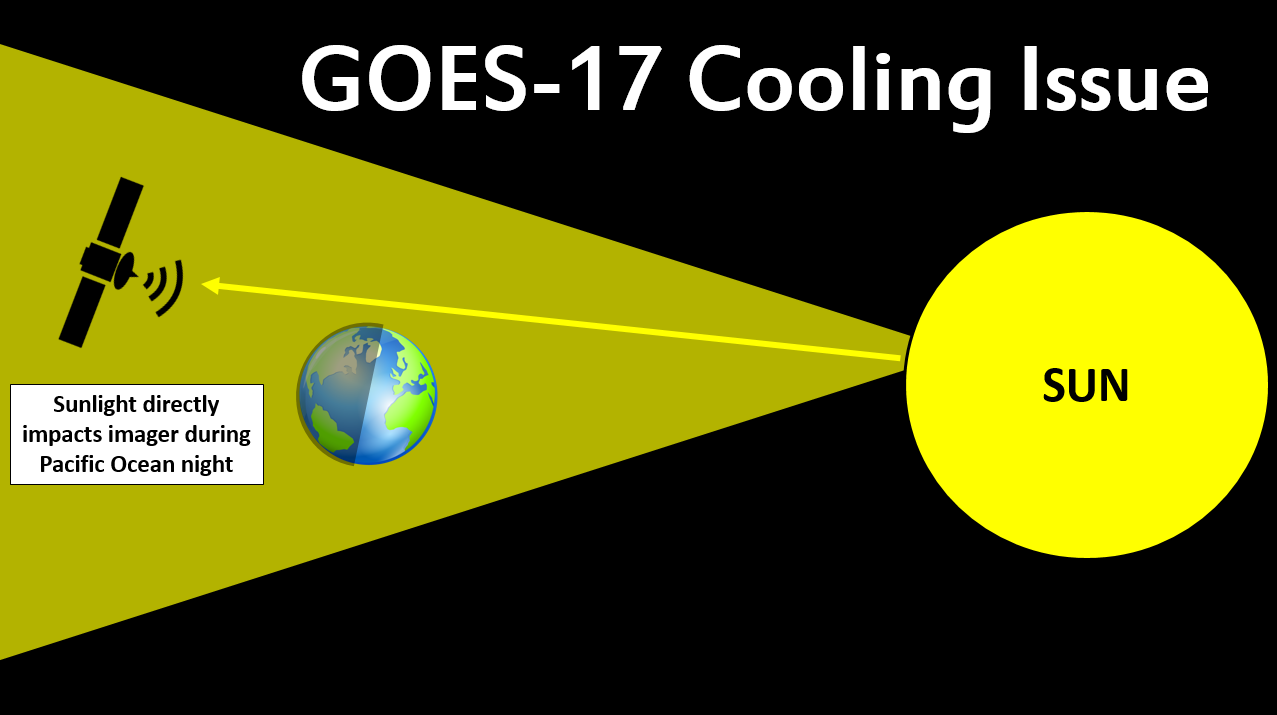

Sadly, it’s not all good news with GOES-West. Shortly after its March 1, 2018 launch, a hardware issue was discovered with the imager’s cooling system. In order to detect the minuscule infrared signal coming from Earth, the sensor itself must be cooled to extremely cold temperatures (around -350°F) in order to prevent the sensor from measuring its own heat signature. Initially, it was feared that as much as 20% of the data from GOES-17 would be lost due to the cooling issue. This would have been devastating considering that the satellite’s budget numbers in the billions of dollars. Fortunately, after many months of adjustments, it is now believed that only about 3% of data will be lost. Still disappointing, but great considering all possible outcomes. The precise amount of lost data will vary based on the time of year and will mainly interrupt things during the overnight hours. The simplistic diagram below shows why this is the case.

Basically, the direct sunlight that hits the imager at night pushes the inefficient cooling system the hardest. The imager gets too warm and the entire signal from Earth gets saturated by the satellite’s own heat signature. Nearly all of the infrared bands (13 out of the 16 in total) are impacted by the cooling issue to some extent. The animation below shows GOES-West mid-level water vapor from today (Band #9). The data is completely useless until about 1600Z, or about 9:00 AM Mountain Time. It’s not ideal, but it is something we will have to live with.

GOES-West mid-level water vapor animation from February 15, 2019. The cooling issue makes the data useless during the overnight hours.

For the next several months, GOES-17 will collect data in tandem with its co-located predecessor, GOES-15, which launched in 2010. The overlap will allow scientists and engineers to make sure that GOES-17 is performing adequately before the older GOES-15 satellite gets placed in “space storage” as a failover.

Despite its flaws, GOES-West is constantly watching down on us. We look forward to more stunning Earth observations in the years to come! Feel free to browse real-time GOES-West imagery at your leisure over at the CIRA GOES website or the NOAA website.

Share this post:

.